LOST SOULS OF THE PEYOTE TRAIL

(published in National Geographic Adventure)

I am camping alone in the Huichol Indians’ sacred peyote desert of Wirikuta, and I hear a sound I can’t account for. A strange rumbling that starts whenever I move, like the sound of a great wind, though there is no breeze, only the kind of silence you find in deserts—a silence so complete that speaking feels like blasphemy. The Huichol believe that the souls of their dead come here. They think that the gods are everywhere, watching. Huichol primeros—first-timers to Wirikuta—who come on one of the annual peyote pilgrimages, don’t see the desert I see but an indescribably brilliant paradise where only the most powerful gods live. They must cover their eyes from the brilliance, and so the shamans lead them blindfolded and conduct a special ceremony so that the primeros can witness it safely. The magic, I have been told, is otherwise too much for them.

I see no magic. Only the mesquite, the creosote bushes looking half dead, the prickly pear, agave, and yuccas of this part of Mexico’s Chihuahuan Desert. There is no sign of any kind of paradise. Just desert scrub. But then again, I have been taught my whole life that magic does not exist. It has been relegated to the imaginings of childhood, to the Tolkein novels and the tales of Narnia. But I look hard now at the mesquite, the prickly pear. I try to imagine a paradise full of gods. The dusk settles upon the desert, sealing me in beneath a wrap of fog. It becomes cold, and I retreat to my sleeping bag and pull it around me. I hear the rumbling again, and terror holds me. I turn on my side and hear it again. And again as I turn my head…

I laugh. I’ve been frightened by the sound of my own inner ears.

*

It is not an easy thing to find peyote—anyone will tell you that. A scientist would say that this is because it lies close to the ground, usually camouflaged by a creosote or mesquite bush. The cactus itself is the size of a silver dollar and the green-gray color of desert brush. It has no spines to protect it from predators, and so it produces a powerful chemical, mescaline, that when ingested will cause an animal to be forever repulsed by it. A scientist would emphasize that the cactus is otherwise a helpless plant, and only its small, elusive nature saves it from illegal harvesting by humans and, thus, extinction.

But the Huichol Indian would give an entirely different story. He would say that the peyote’s spirit—for every peyote plant has a spirit—knows the heart of anyone who goes in search of it, and that if one’s intention is bad, the plant will turn invisible, will hide. Only a knowledgeable Huichol shaman will be able to perform the proper ceremonies in order to coax the peyote to reappear.

I don’t know what to think. My brother, a scientist, is credited in Guinness Book of World Records with discovering the world’s tallest cactus, yet it took him three days to find a single peyote button in Wirikuta. I have nearly convinced myself that I will find none at all. Still, I drive into the heart of peyote country, determined to find some. The Huichol, of course, would see this as a test to determine where I stand in the spirit realm. If my heart is pure and the gods like me, the plant will allow me to find it.

I probably have a number of strikes against me, coming as I do from a family of hard-core atheists who have always viewed belief in such matters as an egregious character flaw. Yet somehow, I became spiritual. It happened slowly, over my college years. The so-called coincidences that felt too much like serendipity. The uncanny power of intention. I found that I could no longer dismiss what I was discovering, so that the dogma of my parents became inadequate to explain the world and my place in it. I sensed there was more.

And then I started reading about the isolated Huichol of Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental, with their complex relationship to peyote—a psychotropic cactus touted as a teacher that can “open the doors to reality”—and I found a people who claim access to higher forms of knowledge that Euro-centric societies can hardly fathom. Just imagine: a people as committed to understanding the realm of gods and spirits, the time-bending channels of past and future, as my American culture has been to its chemistry and calculus.

I park my car and head off into the desert. I start looking under mesquite and creosote bushes, the air thick with the spicy-sweet scent of the desert. I’m amused by this impromptu search, by my lack of qualifications. “Look very carefully,” I’ve written on a notepad. I look. Carefully. Under each bush that crosses my path. Already it seems hopeless. I reach a small rise and see the desert trailing off to the west, agave and yuccas piercing the spread of horizon.

“This is impossible,” I say out loud.

I feel a strange compulsion all of a sudden. That is exactly how it feels—a compulsion—and my gaze is being tugged to a spot behind me. There in the dirt beneath a mesquite bush I have already closely checked and dismissed sit six little peyote buttons. I am amazed to see them; I can hardly believe they’re real. I kneel down to touch one. Its green-gray skin feels tough yet yielding, like the skin of a person’s heel.

I look at my watch and discover that I have found peyote in less than 15 minutes.

*

Sooner or later, the peyote seekers all end up in Real de Catorce. The town clings to a mountainside at 9,000 feet, sheltering a population of barely 1,500 people. As the gateway to the Wirikuta desert, where the Huichol come each year to harvest peyote for their ceremonies, it is one of those hapless towns on the verge of being taken over by the tourist industry. An old silver-mining center, it was all but abandoned when the price of silver dropped in the early 1900s. The former inhabitants left behind steep cobblestone streets lined with dilapidated Spanish-colonial houses and ghost towns littering the hillsides. But the old stucco church of St. Francis of Assisi remains; every 15 minutes its bell tower imposes the time on a citizenry that doesn’t like to wear watches. Foreigners—especially the Swiss—were quick to see the charm and move in. Now there are coffee shops and a cinema, art galleries and restaurants. Only the mining tunnel that cuts through a mountain to Real restricts the tourists, the small number of parking spaces at its end limiting visitors. But Hollywood got in, of course, filming The Mexican here. Framed photos of Brad Pitt or Julia Roberts now compete for wall space with the Virgin of Guadalupe and the saints.

I’m talking with Viviana, who works in a tourist boutique in Real. She is 25, an Italian anthropology graduate student with dark-blond hair, tired eyes. She says she came to Real to study the Huichol. I’ve learned one thing: Where there are Huichol, there will be anthropologists. It is a curious love affair, as the Huichol are notoriously hostile toward outsiders and reluctant to share information with even the most dogged of anthropologists. When I ask Viviana why she doesn’t study the Yanomami, say, or the Inuit, she laughs.

“Because the Huichol are the only people who really keep their traditions alive,” she says. “And also, they use the peyote.”

Outside, as if on cue, an old VW van with California plates charges up the cobblestone road—a vision straight out of the sixties. It’s packed with young gringos in dreadlocks, wearing colorful hemp fabrics; the roof rack is overloaded with dusty backpacks, and a woman with long, tangled brown hair sits cross-legged amid them, smiling benevolently at all who pass below, like some bedraggled Buddha.

I ask Viviana if it’s a problem, outsiders coming here to the Huichol sacred desert, taking peyote, not respecting it.

“Many people think it’s just a drug to enjoy,” she says. “They don’t know that the peyote is a spirit that shows you what you have inside. So they take it, and they have a bad experience.”

I’ve seen the people she’s referring to. Not so much the norteamericanos looking like they’ve just come from a Dead concert, but the Mexican teenagers from the big cities of Guadalajara or Monterrey, who stream to Wirikuta by the truckloads to experience peyote’s world-renowned “high.”

It has become a booming business, that peyote high. Enterprising mestizos in search of cash will arrange trips to the desert so that the city kids can build a bonfire and take peyote. They sell their peyote powdered, dried, fresh, in tea, blended with soda, juice. The whole idea is to help their customers get it down, somehow, to obscure the notoriously bitter, unpalatable taste. What one mustn’t forget, though, is that the peyote spirit knows who is sincere and who is not. The kids taking it just to get high are cursed with a “bad trip” of terrifying images, vomiting, pissing on themselves. Such kids have even shown up on the streets of Real, convinced that they’re dying and begging for their parents. To Viviana—and all those who believe—this is merely the peyote mirroring the nature of their souls, showing them their own inner emptiness and pettiness. Because the peyote never lies. It deals only in truths.

“But if your heart is good, peyote is a very generous spirit,” Viviana tells me. “It can open doors that we normally keep closed because we don’t want to see things. It takes you out of the world, into another dimension.”

Her weary eyes become animated as she tells me this. She says that she was skeptical of it all when she first came to Real, but then she received a healing from a Huichol shaman. The man was able to look into her soul. He saw things about her that no one else has. He woke up her spirit and taught her about peyote.

“And did he cure you?” I ask her.

She smiles for a moment, embarrassed. “Yes. I felt serenity because of him. I will stay in this town for as long as I can, so the Huichol shaman will keep these feelings alive in me.”

She adds, almost as an afterthought, that she’s pregnant. She pats her abdomen, and I can see that she’s showing; she says her Mexican boyfriend is the father. Yes, she will be in Real a long time.

“Congratulations about the baby,” I tell her.

She might not have heard. Frowning, she leans over to light herself a cigarette.

*

I receive good news: Chintito is in town. Many consider him the most powerful Huichol shaman alive, perhaps one of the greatest indigenous healers in the world. Consequently, he is a busy man, wanted all over Mexico. People, I am told, will flock to wherever he is. He is that powerful. That in touch with the gods.

I want to find him and receive a “curing,” find out what needs fixing in me. It’s said that he goes to the desert, takes peyote, and the gods tell him all your past mistakes and regrets, your foibles, your fears. The gods arm him with a blueprint of your soul, and he returns as a kind of shepherd, guiding you to truth.

I am as curious about Chintito as anthropologist and New Age guru, Carlos Castaneda, must have about the man he called Don Juan Matus. In 1968, Castaneda made the Yaqui Indian sorcerer famous in his book The Teachings of Don Juan. In that book and the ones to follow, Don Juan Matus uses psychotropic plants—particularly peyote—to teach Castaneda how to drop his scientific reasoning and fully enter "non-ordinary" reality by using techniques that closely resemble those of Huichol shamans. And as more and more people suffer from comfortable but empty lives, the Native American mind-body panacea of peyote may loom as a kind of Holy Grail or last-ditch cure. What therapy cannot solve, peyote will.

I find Chintito in a hotel lobby. He is a midget, barely three feet tall. To the Huichol, his small stature is propitious, a sign that he has been specially selected by the gods. And he is the first Huichol I’ve ever seen. He wears white cotton clothing elaborately embroidered with fluorescent-colored thread in the designs of deer, flowers, peyote. Beside him is a Huichol woven-straw sombrero decorated with tufts of feathers, colorful pom-pom balls, and beadwork frills. This is a Huichol man’s everyday attire—such ornate, pristine white clothes. They believe that if they adorn themselves as colorfully and as beautifully as possible, they will please the gods and bring favor upon themselves.

Chintito walks up to me, hands clasped before him, eyes bright and clear. I was told that he is in his 60s, but his hair is jet black, and he moves with the agility of a child. We go to my hotel room for the curing. He brings a couple of rectangular straw baskets, telling me that they contain his healing objects: arrows, eagle-feather wands, magic stones, and mirrors. I lie down on the bed as instructed. I haven’t told him anything about myself; he hasn’t asked. I wonder if I ought to mention the nausea I’ve had for the past few days, but now he stands beside me. He looks up thoughtfully, as if receiving silent intelligence, and nods sharply. Suddenly, he spits—two short, quick bursts onto his palms—and lifts the bottom of my shirt. Before I can say anything, he is swirling his saliva-moistened hands over my stomach. He repeats the process. I feel a scalding heat where his palms have touched my skin, and I sit up, alarmed. He smiles and coaxes me down again. He says there is something wrong with my stomach, and he is fixing it for me.

My impulse is not to believe any of this. My impulse is to find some scientific explanation for the burning feeling his palms have left behind, and the fact that he knew about my stomach pain. But I can’t find an explanation. None of this makes sense from my experience. And while just a couple of hours ago, I was prepared to start a regimen of antibiotics for my stomach problem, now there isn’t a stomach problem. Placebo effect or honest-to-God shamanic cure? At this point I don’t care. All I know is that the pain is gone.

But the Huichol don’t stop with the body. They will tell you that it is inseparable from the spirit, and to cure one, you must cure the other. Chintito seems to have a tall order, then, cleaning all the impurities from my psyche, those years of struggling to understand and accept who I am. He looks thoughtfully skyward again, his mouth moving, perhaps chanting something. Again he nods sharply, his eyes distant, intense. He leans over the top of my head and blows there with all his force, to “clean out my inner spirit.”

He steps back and says he’s learned about another, even stranger problem with my stomach. I think I know what he means. I explain that I get stress-related problems there.

He doesn’t understand what I mean by “stress.”

“I have a lot of anxiety,” I tell him. “Ansiedad.” I struggle to come up with the best word in Spanish. I point to my stomach and curl my fingers into a tight fist. “It feels like this.”

His placid face shows hints of amused affection, such as a parent would have for a bumbling child. “Inquietud,” he says, nodding. “You worry about things.” He tells me to come back in five days with a bottle of water, and he will make medicine to cure it.

*

Five days later, I meet with Chintito again. I remind him about the “medicine” he has promised to make and hand him a small bottle of water. He opens a tiny wicker basket. Using the tip of an eagle feather, he mixes something inside it. When I look to see what it is, I discover that the basket is empty. Empty to me, anyway. And Chintito might be the most accomplished mime in the world from the way he mixes the invisible contents, being careful to scrape the sides and tap powder away from the edges. Occasionally, he reaches skyward with his eagle feathers to draw down additional ingredients, adding them deftly with swift movements of the hand. Finally, with the utmost care, he pours the invisible concoction into the water bottle and shakes it. His eyes follow something around inside.

“If you drink this,” he says, “you will not have inquietud stomach problems.”

I consider it: an actual cure for the stomachaches and tightness.

Chintito explains that when there is only an inch of liquid left, I must refill it with water. In this way, my “medicine” will last indefinitely. I must always shake the bottle, too, to stir up the medicine resting on the bottom—magic medicine is, apparently, heavier than water.

I still don’t see anything in the water, though. And it is such a sorry vessel for a magic potion: a nondescript Sam’s Choice water bottle from Wal-Mart.

Chintito announces that while he was out in the Wirikuta desert, the gods of the four directions told him about me. They saw my future, and they think I need a man.

“I need a man?”

“So I told them I will bring you a boyfriend.” He nods, as if it has already been done.

“You’ll need a lot of magic for that one,” I say.

He says the gods have told him what my problem is: I haven’t been looking in my heart to see what type of man I truly want—a common mistake. So of course the gods have been bringing me the wrong men. In the future, I will have to be very specific and tell them exactly what type I’m looking for.

“And this will work?” I ask him.

“Of course.” His clear eyes look at me. I can see that he’s absolutely serious.

But perhaps because he sees my disbelief, he starts to describe, with alarming specificity, the nature of my past relationships. He says the gods have told him all this about me, and if I go back to the desert and eat the peyote I found, they will tell me much more. My skin is tingling: He knows about the peyote. Somehow.

“You must go back to the desert and cut that peyote and bring it to me,” he says. “I will bless it so that the peyote spirit will be kind to you when you take it.”

Chintito gives me very specific instructions for picking the peyote, saying he will wait here for me until I return. Dutifully, I leave to do what he has said, feeling not unlike a female Castaneda reluctantly following Don Juan’s bidding. But I want this peyote to know that I’m sincere—presuming, of course, it can know such things.

When I find the peyote again, I light a candle as an offering. I apologize before cutting it, and I make sure I remove it no more than an inch below the soil so it can regenerate itself. Never, Chintito warned, under any circumstances, should you pull out peyote by its root, which is what only disrespectful people do, killing the plant.

I return to Real de Catorce with the peyote. Chintito waves his eagle-feather wand over them and touches a small one to his magic mirror and then to my legs and hands, representing the Huichol’s four cardinal points, and to my forehead for the sacred center. When he’s finished, he says that the peyote will now tell me anything I want to know about myself. All I have to do is ask.

But I admit that I’m scared to ask. Though I strictly followed Chintito’s instructions, and he blessed the peyote for me, I’m still uneasy about it. I wonder if it will make me sick—or worse. And what will it tell me about myself, what truths I’m not yet prepared to hear? I wrap up the peyote and leave it in Wirikuta where I found it, deciding I’ll come back for it later.

*

I drive southwest. Mexico’s High Desert country rolls past as I take Highway 54 toward Zacatecas and the Huichol homeland in the southern end of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Yuccas grow as big as trees down here, reaching spiked arms toward one another like the otherworldly inhabitants of a Dr. Seuss book. I see a toddler in a miniature cowboy hat and boots attempting to lasso a stallion ten times his size. I see boys riding bareback, three to a horse, bare feet dangling. A horse culture still remains, even with the government’s new superhighway cutting the distances to hours rather than days.

This is the same route Westerners have followed on their own Castaneda-like journeys—people who hope to find themselves a real-life Don Juan among the Huichol, someone like Chintito, who might tell them about themselves and their purpose in life. It isn’t a new phenomenon, non-Indians turning to indigenous peoples for some glimmer of why they’re here and what it all means. Beneath such searching is an intriguing mystery: that there is something so fundamentally lacking in the lives of some people that they are driven to look for fulfillment elsewhere. I’m determined to find out what they’re seeking.

I arrive at the office of Susana Eger Valadez, an American anthropologist married to a Huichol. She is the director of the Huichol Center for Cultural Survival and Traditional Arts in the small desert outpost of Huejuquilla el Alto, spending the last 21 years of her life running this charity organization, which provides medical care, schooling in the Huichol language, and livelihoods for single mothers. She and her center must stand up to a goliath of outside forces—evangelists, big business, alcohol—with only miniscule funding from donors and the sale of Huichol crafts.

I ask her what she thinks the world will lose if Huichol culture is destroyed, and her amiable expression becomes sober.

“We are about to witness the fall of the last great pre-Columbian civilization,” she tells me. “They have a map to a dimension of consciousness that Western culture has very little idea even exists. I think people have an innate sense that there are other dimensions of reality, other ways for our spirits to connect with our spiritual essence and obtain the answers to the mysteries that surround our existence, but the Huichols have created a step-by-step formula to harvest and cultivate this knowledge.”

We’re greeted by Matsua, a Huichol shaman, and his wife. He wears the finely embroidered white clothing; his wife also dresses traditionally, in a long, bright-green skirt, turquoise blouse, and the distinctive Huichol head scarf, a rikuri, made from two bandannas sewn together. She also sports beaded necklaces and bracelets with deer and peyote motifs.

As I take a drink from my water bottle, they astonish me by leaning forward and pointing at it.

“There is medicine in it,” Matsua says with surprise. His wife nods; she sees it, too.

When I shake the bottle, Matsua’s eyes widen. He tells me almost exactly what Chintito said: that yellow-colored “medicine” is floating around and falling heavily to the bottom, where it fizzes.

I strain to glimpse what he sees. I consider the idea that certain people—native people born into a spirituality that doesn’t separate the godly from the earthly realm—can connect with powers we non-Indians can’t. What looks like clear water to me is “medicine” to Matsua. He sees the magic with his two eyes. He can point it out to me, describe its color, its consistency. Do I say that he is looking at nothing? Is it arrogance to declare that my perception is the correct one? Or are my faculties for perception underdeveloped—stunted, even—by Western notions of reality? I realize that if the Huichols lose their cultural traditions, as Eger Valadez fears, they will lose this too: their ability to see what I cannot. That view of another, perhaps better, world.

*

I sit in the front seat of a 1974 Chevy truck, beside Rachel, a photographer, and Marciano, our driver and translator. We are heading into Huichol land in the forbidding mountains of the Sierra Madre Occidental. Tagging along in back are two young women studying the Huichol, anthropology graduate students from a Mexican university. When I ask one of them, Maryanna, why she’s interested in the Huichol, she shrugs. “We have to pick one of four tribes for our class fieldwork,” she says. “The Huichols were my last choice.”

The old truck roars. We climb higher into the mountains. Foothills reach far into the desert below, forming a series of deep canyons. These mountains show no sign of civilization except for our crude road plying into them. Prickly pear and paloverde give way to stunted oaks and pines. Quite suddenly, it becomes cold. We find ourselves skirting the tops of mountains, the tree line breaking away to reveal the slopes of the 10,000-foot-high Sierra Madre falling away on either side. It is a Mexico I could have barely imagined, a country so unmolested, so pure, that I feel as if I am eavesdropping on some undiscovered world. Here is where the conquistadors gave up their chase of the Huichol, in these deep ravines and gorges, amid these unyielding mountains.

The story of the Huichol has been one of success against great odds. They survived centuries of European invasion—Spanish soldiers, Franciscan monks, gold seekers, ranchers, Mexican bureaucrats—with only the most minimal of cultural damage. Their strategy was to strike out at the intruders, then retreat into the barrancas, these rough canyon lands where no one could follow. It worked. Except for a few intrepid missionaries and ethnologists, the world pretty much left them alone. It was only when the Mexican government built roads and airstrips in their country, in the latter half of the 20th century, that the threat of outside intrusion became real again.

Still, for a people numbering around 20,000, they have entered the 21st century achieving the extraordinary: They remain animists, practicing an ancient religion that has its roots in their hunter-gatherer days in the high desert. It is this remarkable spiritual tradition that has evangelists as far away as Canada planning new offensives to target the Huichol deep in their inaccessible canyons. Radios are now parachuted down onto people’s doorsteps or onto the roofs of sacred temples. They can be tuned to only one station, to a single repeated message: “Jesus Christ has come to save you.” The rare Huichol who convert—labeled derisively as Aleluyas by their fellows—could face corporal punishment, razed homes, and rejection from the tribe. Such responses have caused the Huichol to be described as a fiercely independent people and persuaded outsiders not to enter their country.

I was advised against doing the same by a couple of Texas reporters, as one of their own was recently murdered up here. Philip True, of the San Antonio Express-News, was an open admirer of the Huichol and wanted to write a laudatory article about them. Thus began a ten-day solo journey across their country from which he never returned. Two Huichol men later confessed to strangling him to death and burying him in his sleeping bag—all because he hadn’t asked for their permission to hike and take photos.

This does not bode well, but I have done everything I can to ensure my and Rachel’s safety. For one thing, I’ve associated myself with Marciano, a Huichol, as well as with a shaman named Alejandro. Though Alejandro has revealed an early-morning appetite for tequila, he is part of the inner circle of shamans in the town we’re heading to, San Andrés Cohamiata. I have been told that he has good standing and authority there and will take us under his wing—for a price. I call him the 200 dollar man.

*

San Andrés Cohamiata was named by the Spanish in the early 18th century, though the Huichol still call it Tatéi Ki’ye, “House of Our Mother.” The village is composed of mostly thatched-roofed adobe dwellings built around a large dirt square. In many of these homes, I see strings of dried peyote hanging from the rafters, awaiting medicinal or spiritual use.

Many Huichol regularly use peyote to give them energy when they’ve become fatigued while hunting or working, though only a small amount is consumed for this purpose. During ceremonies, however, peyote is taken in large quantities to facilitate communication with the gods. In my jeans and T-shirt, I feel entirely out of place here. Women in long, bright skirts and head scarves sweep the dirt stoops of their houses or grind maize for tortillas. Men crowd around fires in the square, all wearing embroidered white clothing and lavishly decorated sombreros. Musicians play handmade fiddles, while shamans sit on special bamboo stools and sing to Tatewari, Grandfather Fire, who oversees all ceremonies. We’ve arrived in the middle of the Cambio de las Varas ceremony, which celebrates the yearly replacement of the village officers. Marciano tells me that the gods choose the new officials and relay their choices to the shamans. This process, sacred and auspicious, can be sanctified only by blood and song.

Rachel and I meet with Francisco, the 69-year-old governor of San Andrés, for permission to witness and photograph the ceremony. A powerful shaman, he stands regally before us, his silver hair grazing his shoulders, his bluish cataracted eyes seeming to glow as he studies us. He is worried that Rachel’s photos will end up on postcards in some Guadalajara tourist shop—an insult that other outsiders have dealt him. But we assure him of our good intentions, and he finally agrees to let us witness the ceremony, giving us the all-important safety net of official permission.

I walk to one of the village’s xirixi, or ancestor god-houses, where the ceremony will be starting. It is a round wall of stone in which the principal shaman calls for the assistance of Tatewari and his helper, Kauyumari, the indispensable half-man, half-deer deity that acts as an intermediary between mortals and gods. Such communication is impossible, however, without the sacrificing of goats. A man slashes some animals’ necks and collects their blood in plastic Fanta bottles.

“The gods are telling us to change the officers, so we do,” a Huichol, José, explains.

He says that the sacrificial blood gives power to the shamans’ wands and other objects. Without the blood—which contains the animals’ life force—the objects are too weak to perform their spiritual tasks. Prayer arrows can’t reach the gods. Messages from the shamans remain unheard. But blood itself marks an important moment: The gods are now present.

“They are everywhere,” Jose tells me. He can’t see or speak to them, though—he’s not a shaman. But he feels their presence. All the Huichol feel them. And it is an awesome presence that makes his eyes grow wide.

I can’t see or feel anything but a frenetic sort of energy that seems to be overtaking us all. I’m swept up into a crowd that heads toward the town’s main temple. We stop for what will be the first of five times, each spot marking one of the five sacred points of Huichol cosmology. Musicians follow the circling entourage and play frenzied music. The families of the old and new officers take seats, and a chanting shaman blesses both groups, holding over them his eagle-feather wand, shots of distilled alcohol and maize beer, and ears of sacred corn. The Huichol pay constant homage to a trinity of maize, deer, and peyote; the three interconnected and sacred elements, symbolically visible everywhere, ensure their very existence as a people. A shaman’s stool is placed in the midst of the throng, dried skins of deer heads tied to it. This reminds everyone of Kauyumari’s presence and role as go-between for the shamans—not honoring him could bring devastation to the village. The shamans anoint tips of arrows with animal blood and touch them to the deer masks as an offering. Always, there is consideration for the gods, and I wonder if some outsiders are drawn to the Huichol because they want to experience this “supernatural” realm. Yet what might seem supernatural to me is normal to them. They know of no other existence except one in which mortal and mystical realms are indivisible.

We enter the main temple, the crowd joyous, rowdy and drunk on the beer sold from a truck in the village square. Several bulls lie on the dirt floor before me, legs firmly trussed, each one to be killed as an offering to a different god. A man with a specially blessed knife slowly cuts into the neck of one animal. Its blood must be carefully collected while the bull is still alive; it takes a long time to die. Watching with moist eyes, I wonder how many people have witnessed death in this way, the life force, the energy, of a creature being drained before their eyes. Does the energy go elsewhere, as the Huichol believe? I can’t say.

One man, his once brilliant white pants completely soaked with gore, wipes bloody hands on the face of a life-size Jesus on a cross that was removed from the temple’s dais. Confused, I ask Marciano why the animist Huichol are smearing a Christ statue with bull’s blood.

“That’s not Jesus,” he says. “It represents the village patron, San Andrés.” He explains that when the Spanish finally made it here, they introduced Christian saints. The Huichol respected the power of these “deities” and so added them to their own crowded pantheon.

The bull just killed in San Andrés’s honor is dragged from the temple. Flocks of rangy dogs descend upon the blood trails and lick feverishly. So many empty Modesto beer cans are starting to pile up around the cattle still awaiting slaughter that the shamans’ helpers must roll the animals over them. Outside the temple, I see people passed out on the ground, and I recognize one as a shaman I had talked to earlier. Many Huichol believe that if the governor or shamans don’t fulfill their secular and spiritual obligations, the gods will punish an entire village with alcoholism. I wonder if that’s been occurring in San Andrés.

Rachel joins me in the temple, shaken. She points to a red mark on her forehead: A man struck her in the head with her camera. Other men tried to seize her gear, accusing her of having no permission to be here. But what has her the most distressed is that no one in the crowd did anything to help—not even Marciano or Alejandro.

We head out into the throng. Alejandro, our $200 protector, is pretending he doesn’t know us. I don’t see the governor or elders anywhere. A man in a green jacket comes over to us. He grabs at Rachel’s cameras, speaks to her threateningly. I step between them and forcibly hold him off. He is up close to me now, his face inches from mine. Our eyes link. I fear I may actually have to fight this man to protect myself, and it is not this that scares me—he is drunk and shorter than I—but the thought of what other Huichol might do if one of my punches sends him to the ground.

Thankfully, Marciano comes over to help out Rachel. I retreat to the truck, thinking of how journalist Philip True’s plight might have resembled our situation. I can easily imagine the man in the green jacket rounding up a friend or two and coming after me or Rachel. When I head to a nearby field to go to the bathroom, I carry a knife up one sleeve. No chances. The situation is fast deteriorating as the crowd gets drunker and more belligerent. Federales with submachine guns are being brought in now to keep the peace, and I know we have to get out of here.

I wait, on edge, through the late afternoon. And then the inevitable occurs: The man in the green jacket has persuaded the legal authorities to deny us permission to be here. Rachel must stop taking pictures immediately. They want us out.

*

The next morning we creep into the village to try to patch things up with the governor. A group of elders finds us. They’re contrite, apologizing about the man who struck Rachel; they say they will punish him. They tell us that the village’s legal committee hadn’t known about the permission we got and so disapproved of our being here. But everything is all right now. We can stay, with their blessing.

I don’t know what to make of this sudden change of heart. I’m still wary. But there is a playful feeling to today’s events that distracts me. We’re just in time for an afternoon procession to honor the gods and the new officers, in which the people of the village pass on gifts of food and clay pots full of nawa—fermented maize. The musicians begin playing their fiddles and cellos. Men hoist onto their backs raw cattle legs from the animals sacrificed yesterday. Tied to this meat are various delicacies—fruit, cookies, Instant Lunch ramen noodles, bottles of Fanta, maize cakes wrapped in corn husks. Anything that might please the gods. People gather, holding sugarcane stalks decorated with food bundles. The parade is about to start, and a mestiza missionary woman walks to the front of the group. She wears a long gray smock and a hint of amusement on her lips as she watches the proceedings. I go up to greet her, and she introduces herself as Mariel.

“Do you wish this was a Christian ceremony?” I ask her.

“It is a Christian ceremony,” she says. A man wearing a slab of raw cow ribs on his back walks past. “Christ is telling them to do this ceremony. If they don’t, He will punish them.”

Only yesterday, José explained to me that “the gods” tell the Huichol to perform this ceremony. Mariel’s is an interesting form of rationalization that I’ve heard before from missionaries around the world: if you can’t eradicate the tradition, claim it as your own.

I’m surprised to see a tall gringo with blond hair holding one of the sugarcane stalks. He smiles at the people around him and takes a place in the front row of the parade as it moves across the town square. I approach him when the crowd finally disperses. He tells me his name is David, that he’s 29, from Italy. Beside him is a woman about the same age, Michelle, with a ruddy face and a placid smile.

When I ask them what they’re doing here, they look at each other and shrug.

“I don’t know,” David says, staring at me, childlike, with large blue eyes.

“Are you traveling,” I ask him.

They look at each other. “No,” he says, smiling shyly, almost apologetically.

“Are you scientists? Backpackers? What?”

David looks at his feet. “I don’t know,” he says. “We’re not anything.”

It turns out though, that they were something back in Italy: fruit pickers. But then David discovered Castaneda’s writings and became inspired to try peyote. He came alone to Mexico a year ago, went to the sacred desert, ate some peyote. And that was when the most extraordinary event of his life occurred: He talked to God in the desert; he found Truth. He ended up returning to Italy only to come back to Mexico with Michelle, so that they could live with the Huichol, this “peyote people,” and learn even more about themselves.

I consider the idea of David’s “Truth.” It is such a loaded term, of course, but I sense that he has found something which goes beyond the belief systems that pass as “truth” for many people in the West. He has experienced some kind of truth that is deeply spiritual and universal. I suddenly realize that I’m envious of David. I see how difficult it is for myself and people from my Western culture to feel a sense of belonging and peace within themselves. And so some go searching for it among groups like the Huichol. Some will search forever.

As I leave the Italians, I discover that Marciano has overheard the whole conversation. Usually stoic-faced and reticent, he is laughing now. He tells me that David has obviously gone crazy.

“But he said he found Truth,” I say.

“That’s why he’s gone crazy. How can you not know your place in the world? He doesn’t know where he belongs. He’s lost. But a Huichol always knows who he is and why he’s here.”

“Huichols never get confused about that?” I ask.

I see the flash of a grin for a dumb question. “No. A Huichol is never confused. When you believe in something, and when you have faith and traditions, you know what you’re doing and you have purpose. Huichols know why and what they do everything for.”

“Do you think the Huichols can teach David something if he stays with them?”

Marciano shakes his head. “You can’t just go somewhere and buy the essence or purpose or origin of yourself. He’s here because he thinks he can become like a Huichol, but it’s not possible. He’s an Italian. I don’t understand people like him. He’s lost his mind.”

*

And here I am back in the Wirikuta desert, and I suppose it could be said that I’m searching for my own Truth. Not the Huichol’s truth, or the truth of some other people or place. Just my own. I eat the peyote that Chintito blessed for me, and it tastes pleasantly medicinal, like a cross between aloe vera and alfalfa sprouts. The Huichol believe that you can lose your soul when you take peyote here—either you will reconnect with the forces of your ancestors or spiral into primordial chaos. Yet everything feels fine to me. I feel safe.

Above, the stars get brighter, the mesquite, sharper. I seem to be sinking deep into the earth; I’m experiencing the greatest sense of peace and security I have ever felt, as if returned to the womb. All I want to do is sleep….

I wake. The moon is directly over me now. I wonder if I’ve done all this right. There has been no nausea, no horrible visions. And though I had numerous questions for the peyote, I felt so at ease that I lost them all. Perhaps I made a mistake. Perhaps I didn’t take the right amount. I don’t understand why my questions don’t seem to matter anymore. I’m suspicious of this deep peace.

I’m determined to do this properly, to ask my questions and not fall into that tantalizing sleep again. I eat another, larger button. Before I can word my first question, my abdomen grips up. The moon becomes bright, like an interrogator’s spotlight, and scenes leap out of my past. They begin in childhood, a slide show of images that flicker and die out like ten-second newsreels. I look on with detachment, the peyote forcing me to watch by keeping me just uncomfortable enough so that I can’t retreat into sleep. After a while, I start to understand that all these scenes have one thing in common: They deal with the petty fears and worries that have come to dominate my life. And I must watch them all, and learn.

At last the grip in my abdomen is released, and the show ends. I start to hear the sound of a great wind, just as I had when I camped in this desert for the first time, but now I’m certain it’s coming from outside myself. It’s almost dawn. Fog has settled over the desert, obscuring distances so that I feel entirely alone on earth, confined to a small radius of visible world. I have a terrible hangover, but there is no aching, no nausea or headache. It is a hangover of the soul. I stand up to take my first steps.

|

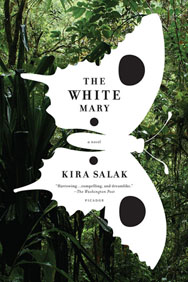

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()