MUNGO MADE ME DO IT: KAYAKING TO TIMBUKTU

(published in National Geographic Adventure;

Anthologized in The Best

American Travel Writing 2003

and The Best Women’s Travel Writing)

In the beginning, all my journeys feel at best ludicrous, at worst insane. This one is no exception. The idea is to paddle nearly 600 miles on the Niger River in a kayak, alone, from the town of Old Ségou to Timbuktu. And now, at the very hour I have decided to leave, a thunderstorm bursts open the skies, sending down apocalyptic rain, washing away the very ground beneath my feet. It is the rainy season in Mali, for which there can be no comparison in the world. Lightning pierces trees, slices across houses. Thunder wracks the skies and pounds the earth like mortar fire, and every living thing huddles in its tenuous shelter, expecting the world to end. Which it doesn’t. At least not this time. So we all give a collective sigh to the salvation of the passing storm as it rumbles its way east, and I survey the river I’m to depart on this morning. Rain or no rain, today is the day for the journey to begin. And no one, not even the oldest in the village, can say for certain whether I’ll get to the end.

“Let’s do it,” I say, leaving the shelter of an adobe hut. My guide from town, Modibo, points to the north, to further storms. He says he will pray for me. It’s the best he can do. To his knowledge, no man has ever completed such a trip, though a few have tried. And certainly no woman has done such a thing. This morning he took me aside and told me he thinks I’m crazy, which I understood as concern, and so I thanked him. He told me that the people of Old Ségou think I’m crazy, too, and that only uncanny good luck will keep me safe. What he doesn’t know is that the worst thing a person can do is to tell me that I can’t do something, because then I’ll want to do it all the more. It may be a failing of mine.

I carry my inflatable kayak through the labyrinthine alleys of Old Ségou, past the small huts melting in the rains, past the huddling goats and the smoke of cooking fires, past people peering out at me from dark entranceways. It is a maze of ancient homes, built and rebuilt after each storm, plastered with the very earth people walk upon. Old Ségou must have looked much the same to Scottish explorer Mungo Park, who left here on the first of his two river journeys 206 years ago to the day—the first such trip made by a Westerner. It is no coincidence that I’ve picked this date, July 22, and this spot to begin my journey. Park is my guarantee of sorts. If he could travel down the Niger, then so can I. Of course Park also died on this river, but so far I’ve managed to overlook that.

I gaze at the Niger through the adobe passageways, staring at waters that began in the mountainous rain forests of Guinea and traveled all this way to central Mali—waters that will flow northeast with me to Timbuktu, cutting through the Sahara only to retreat south, through Niger, on to Nigeria, passing circuitously through mangrove swamps and jungle, resting at last in the Atlantic in the Bight of Benin. But the Niger is more than a river; it is a kind of faith. Bent and plied by Saharan sands, it perseveres more than 2,600 miles from beginning to end through one of the hottest, most desolate regions of the world. And when the rains come each year, it finds new strength of purpose, surging through the sun-baked lands, giving people the boons of crops and livestock and fish, taking nothing, asking nothing. It humbles all who see it.

Thunder again. Hobbled donkeys cower under a new onslaught of rain, ears back, necks craned. Naked children dare one another to touch me, and I make it easy for them, stopping and holding out my arm. They stroke my white skin as if it were velvet, using only the pads of their fingers, then stare at their hands for wet paint.

The rain falls even harder. I stop on the banks of the river near a centuries-old kapok tree under which I imagine Park once took shade. I open my bag, spread out my little red kayak, and start to pump it up. A photographer, who will find me in his motorized boat for a quick photo shoot once every four or five days before disappearing again, feverishly snaps pictures. With the exception of his very rare appearance on the river, I will be entirely alone.

My kayak is nearly inflated. A couple of women nearby, with colorful cloth wraps called pagnes tied tightly about their breasts, gaze at me as if to ask: Who are you and what do you think you’re doing? The Niger churns and slaps the shore, in a surly mood. I don’t pretend to know what I’m doing. Just one thing at a time now: kayak inflated, kayak loaded with my gear, paddles fitted together. Modibo is standing on the bank, watching me.

“I’ll pray for you,” he reminds me.

I balance my gear, adjust the leg straps, get in. Finally, irrevocably, I paddle away.

Before Mungo Park left on his second expedition, he never admitted that he was scared. It is what fascinates me about his journals—his insistence on maintaining an illusion that all was well, even as he began a journey that he knew from his first experience could only beget tragedy. Hostile peoples, unknown rapids, malarial fevers. Hippos and crocodiles. A giant widening of the Niger called Lake Débo to cross, like being set adrift on an inland sea, no sight of land, no way of telling where the river recommences. Forty of his forty-four men dead from sickness, Park himself afflicted with dysentery when he left on this ill-fated trip. And it can boggle the mind, what drives some people to risk their lives for the mute promises of success. It boggles my mind, at least, as I suffer from the same affliction. Already I fear the irrationality of my journey. I fear the very stubbornness that drives me forward.

The Niger erupts in a new storm. Torrential rains. Waves higher than my kayak try to capsize me. But my boat is self-bailing, and I stay afloat. The wind slams the current in reverse, tearing and ripping at the shores, sending spray into my face. I paddle madly, crashing and driving forward inch by inch, or so it seems, arm muscles smarting and rebelling against this journey.

A popping feeling now and a screech of pain. My right arm lurches from a ripped muscle. But this is no time or place for such an injury, so I try to get used to the metronome-like pulses of pain as I fight the river. There is only one direction to go: forward. Always forward. Stopping has become anathema.

*

I often wonder what I seek when I embark on these kinds of trips. There is the pat answer that I tell the people I don’t know: that I’m interested in seeing a place, learning about its people. But then the trip begins, and the hardship comes, and hardship is more honest: It tells us that we don’t have enough patience yet, nor humility, nor gratitude. And we thought that we had. Hardship brings us closer to truth, and thus is more difficult to bear, but from it alone comes compassion. And so I have told the world that it can do what it wants with me if only, by the end, I’ve learned something beyond what I already know. A bargain, then. The journey, my teacher.

The Niger has calmed, returning its beauty to me: a river of smoothest glass, a placidity unbroken by wave or eddy, with islands of lush greenery awaiting me like distant Xanadus. Tiny villages of adobe huts dot the shores, each with its own mud mosque sending squat minarets to the heavens. The late afternoon sun settles complacently over the hills to the west. Paddling becomes a sort of meditation now, a gentle trespassing over a river that slumbers.

Mungo Park is credited with having been the first Westerner to discover the Niger, in 1796, which helped make his ensuing narrative, Travels in the Interior Districts of Africa, a best-seller. But I wonder if the sight of his “majestic Niger” was enough reward for the travails he suffered: the loss of all his possessions, the brutal confinement by the Moors, the half-starved wanderings in the desert. Before quinine was used to fight malaria, travel to West Africa was a virtual death sentence for Europeans. Colonial powers used only their most expendable soldiers to oversee operations on the coast. It wasn’t uncommon for expeditions to lose half their men to fever and dysentery if the natives didn’t get them first. So Park’s ambitious plan to cross what is now Senegal into Mali, then head down the Niger River to Timbuktu, hasn’t a modern-day equivalent. It was beyond gutsy—it was borderline suicidal.

Park wrote that he traveled at the rate of six or seven miles an hour, but I barely travel at one mile an hour, the river preferring—as I do—to loiter in the sun. I lean down in my seat and hang my feet over the sides of the kayak. I eat Turkey Jerky and wrap up my injured arm, part of which has swelled to the size of a lemon.

The Somono fishermen, casting their nets, puzzle over me as I float by.

“Ça va, Madame?” they yell. How’s it going?

Each fisherman brings along a young son to do the paddling. Perched in the backs of the pointed canoes, the boys gape at me, transfixed. They have never seen such a thing. A white woman. Alone. In a red, inflatable boat. Using a two-sided paddle. I’m an even greater novelty because Malian women don’t paddle; it is a man’s job. So there is no good explanation for me, and the people want to understand. They want to see if I’m strong enough for it, if I even know how to use a paddle. They want to determine how sturdy my boat is. They gather on the shore in front of their villages to watch me pass, the kids screaming and jumping in excitement, the women with hands to foreheads to shield the sun as they stare, the men yelling questions in Bambarra which by now I know to mean: “Where did you come from?” “Where is your husband?” And, of course, they will always ask: “Where are you going?”

“Timbuktu!” I call out to the last question. It sounds preposterous to them, because everyone knows that Timbuktu is weeks away and requires paddling across Lake Débo,

somehow, and through rapids and storms. And I am a woman, after all, which makes everything

worse.

“Tombouctou!?!” they always repeat, just to be sure.

“Awo,” I say in the Bambarra I’ve learned. “Yes.”

They shake their heads in disbelief. We wave goodbye, and the whole ritual begins again at the next village. And at the next, and the next after that, kids running after me along the shore, singing out their frantic choruses of “Ça va! Ça va!” I might be the Pope, or someone close. But in between is the peace and silence of the wide river, the sun on me, a breeze licking my toes when I lie back to rest, the current as negligible as a faint breath.

Timbuktu lies somewhere to the northeast, as distant and unimaginable to me as it must have been to Park, who first read about the city in Geographical Historie of Africa. Written in 1526 by a Spanish moor named Leo Africanus, the book described Timbuktu as a veritable El Dorado, a place of higher learning with houses roofed in gold. The city was indeed a bastion of wealth and haut couture, the pearl of West Africa’s great Songhai Empire, home to universities, extensive libraries, one of Africa’s largest and grandest mosques, and a population that may have exceeded 50,000 people. Timbuktu throve off its location as a crossroads of commerce between the great Saharan caravan routes and the Niger River Basin. It was here that men traded Saharan salt for the gold, ivory, and slaves that came from the south. Slavery would become one of Timbuktu’s most lucrative operations, the Arabs giving the Niger the name Neel el Abeed, “River of Slaves.” Slavery still exists here, tacitly, though some Malian officials and anthropologists alike tend to deny this, saying that slavery was abolished when France colonized Mali in the late 1800s. But I carry two gold coins from home, and if I ever get to Timbuktu, I intend to find out the truth, and then, if possible, free someone with them.

Unbeknownst to Europeans of Park’s era, Timbuktu’s exalted stature ended in 1591, when a Moroccan army crossed the Sahara with the most sophisticated weaponry of the time—cannon and muskets—and sacked the golden city in a single day. The raid marked the beginning of a decline from which Timbuktu never recovered. Still, ill-informed Europeans embarked, one after another, for an African El Dorado that no longer existed. There were only two ways to get there, neither very promising: You could risk enslavement or death by trying to cross the great Saharan ocean of sand from the north, or brave the malarial jungles of West Africa and then travel up the Niger. Park’s first journey ushered in the frantic “Timbuctoo Rush” of the early 1800s, and it wasn’t long before the River of Slaves became a highway into a lethal region known as the White Man’s Grave.

*

In the middle of the night, I wake with a start: The bear bell on my kayak is ringing—someone has discovered my boat. From inside my tent pitched on shore, I can hear two men whispering; I can see the beam from their flashlight flickering anxiously about the dark shore. I had hoped that the bell would prove an unnecessary—if not paranoid—precaution on my part, but here we are: the middle of the night, two strange men going through my things, and only a can of Mace and some martial-arts training between me and potential theft and/or bodily harm.

I forget about this sort of thing before I go on these trips. Or, more accurately, I ignore the possibility of this sort of thing happening. It’s hard to anticipate anything when I don’t know a place and its people yet. There are no experts for me to call because no one has done this before. In this case, I don’t even know what tribe I’m dealing with. Fulani or Bambarra? Bozo or Somono? Each has different customs, different ideas of what’s appropriate behavior.

But the men don’t know that I’m alone. And they don’t know that I’m a woman. So I get up, arm myself with a section of a paddle, and burst out of my tent, yelling “Hey!”in a deep, madman’s voice.

It works. They flee in their canoe, paddles making a frenzied splunking sound in the river. I watch in the faint moonlight as they disappear around a bend, sighing in relief, my breath quivering.

But it’s not over yet. About ten minutes later I hear their voices again. And now I see their flashlight beam coming toward me across the savanna. I run to take down my tent and stuff my gear into the kayak. In a matter of minutes, I have all my possessions in the boat and shove off. The men reach my camping spot soon after I leave, and they stand on the shore: two dark figures barely distinguishable from the starless night. I paddle hard over the ghostly, silver-colored waters, the river nearly a mile wide here and no telling how deep.

I stop after a while, sitting back in my seat, letting the waves pull and tug at my boat. All around me: the lapping, quick-silver waters. No sight of land, no suggestion of people. I feel as if I were the last person alive. I’m scared to make a sound, as if even a deep breath might somehow disturb the world’s indifferent slumber. Sleep won’t come, so I just float along to wherever the river wants to take me.

*

After a day of paddling, I decide not to camp by myself again. I will need to spend my first night in a village, though I have no idea how I will be received by the people there. Nervous, I paddle to the only village I can see on an otherwise barren stretch of shoreline. It’s a collection of a few round adobe huts, topped with thatch. Some women, large washtubs balanced on their heads, see me as I paddle over, and they run off to alert the rest of the community. Soon everyone who can walk, run, or crawl is awaiting me on shore.

The children stroke my kayak and stare at me. No one speaks a word of French, so I use some of the Bambarra I’ve learned, discovering that this village is called Siraninkoro, and that the people are Fulani—a herding tribe. I can see their cows grazing nearby, baying to the coming dusk. Park’s 200-year-old narratives act as my guidebook now. I do exactly what he did when he arrived in a new village: I ask for the doogootigi or chief. The people smile and lead me up the mud bank. The chief comes over to greet me. He’s a cordial man with a welcoming smile. Using Park’s narratives as a guide, I sit beside him on his mat, accept his calabash full of foaming cow’s milk straight from the udder, and give him a generous gift of money, asking if I can spend the night. Following this procedure is crucial, Park emphasized, as it secures the chief’s hospitality and patronage, and thus ensures your safety. Things haven’t changed much in 200 years.

The kids fight with each other to have the privilege of helping to carry up my kayak, the red boat held aloft by scores of little hands. As it only weighs twenty-three pounds, they easily carry it above their heads, cheering, and place it beside the chief’s hut. The women crowd around me, speaking in fervent Bambarra. They all wear large gold discs in their ear lobes, the older women also having several such rings up and down each ear. They style their hair in beautiful, elaborate corn rows with tufts of hair sticking up on top. Their skin is light, a dark blue tattoo accentuating the area around their mouths. Here, in this remote village, they bare their breasts with wonderful nonchalance, brightly patterned pagnes covering the areas that Malians consider sexual: the legs and buttocks.

They want to know where my husband is and how many babies I have back home in America. I try my best to explain through signs and broken Bambarra why I have neither, but it takes some time. We’re still discussing it as we eat dinner. I’m afraid we might be discussing it all night, but the women at last declare that it’s bedtime.

We all lie down side by side on foam mattresses spread outside the huts. Mosquito nets stretch overhead, blurring the stars. Fleas hop on my skin; chickens jump on us. I fall asleep to the sound of the old folks snoring, goats nibbling at our feet.

*

Always, at some point in these trips, I suddenly wake up to the reality of what I’m doing. I discover, quite unexpectedly, that I am, in this case, alone in a little red boat in the south Sahara, en route to Timbuktu. Somehow this becomes news to me, and I’m forced to pull over and ponder the implications for the first time. Inevitably, I pull out my map. It tells me that I’m now past the town of Massina, and that my goal of Timbuktu rests so far to the northeast that it actually hides on another section of my map.

My God, I think, but always when it’s too late. As is the case now: A crowd of at least 50 naked children are sprinting over a nearby hill and descending upon my boat.

“Tubabu! Donnez-moi cadeau!” they scream. Hey, whitey! Give me a gift!

Their excitement turns chaotic. Hands pull and grab at the things in my kayak. I take out a bag of dried pineapple slices and throw them in the air, and the mass of bodies flies toward the treats, kids fighting and tearing at one another. I have never seen anything like it, and I paddle away as if for my life.

I wonder when Mungo Park’s moment of realization struck. When he was captured by the Moors and a woman threw urine in his face? When he was so destitute that he was forced to sell locks of his hair as good-luck charms? Or perhaps it didn’t come until the second journey when he found himself in a rotting boat, 40 of his 44 men dead from accident or disease, one of the remaining four men having gone insane, Park himself afflicted with dysentery. “Though I were myself half-dead,” he wrote in his final letter, “I would still persevere; and if I could not succeed in the object of my journey, I would at least die on the Niger.” Why didn’t he turn back? the reader must wonder. What was wrong with the man?

But I’m beginning to understand Park more than ever before. Once the journey starts, there’s no turning back. The journey binds you, it kidnaps and drugs you with images of its end, reached at long last. You picture yourself arriving on that fabled shore. You see everything you promised yourself. For Park, it might have been streets of gold, cool oasis pools, maidens cooing in his ear. For me, it is much simpler: french fries and air-conditioning.

And now another storm is coming, a strong wind blowing directly against me. My paddling slows to a crawl. Dark clouds boom and rattle while great Saharan winds churn up the red soil and paint blood trails across the sky. I rush toward shore. The winds get worse, the river sloshing with three-foot-high whitecaps. It is the Jekyl-Hyde phenomenon of the Niger, the river calm one moment only to burst into waves and rapids the next.

As I lean forward to secure my bags, a huge wave broadsides my boat, flipping it. I fall out and swim to the surface, seeing my kayak bottom up and speeding steadily away. I dive for it and grab its tail, turn it over, and retrieve my paddle, only to see my little backpack—the one with my passport, money, journal—starting to sink nearby.

It is as if my worst fears are being realized, one after the next. But by treading water and holding onto the kayak, I’m able to retrieve the backpack. Pulling myself inside the boat, I fumble to get oriented in the waves, then paddle toward shore with all my strength. Thunder bellows, lightning flashes. I make it to the bank, rain shooting from the sky with such force that the drops sting my skin. I huddle, shaking from adrenaline, and take a tally of what I have lost: two water bottles and some bags of dried fruit, but, mercifully, nothing else. The Niger has won my submission.

*

I reach the town of Mopti, everything completely soaked from my kayak wipeout, and not quite yet recovered from it myself. Physically, I’m wasted. Mentally, I have a new and formidable respect for the wrath of the Niger.

I meet a local man named Assou, a friend of the Peace Corp folks in town. When I tell him what my trip has been like so far, he says I obviously didn’t know about the genies that inhabit the Niger—every Malian knows about them—which explains why I’ve been having problems. He says it’s essential that I enlist these spirits in my cause of reaching Timbuktu, or who knows what tragedies might befall me. At his urging, we head inland to the Bandiagara escarpment to see Yatanu, a Dogon witch, for a consultation about this.

We reach Niry village, where Yatanu lives. It sits high on a rocky plateau, a collection of low adobe dwellings mingling with tall, thatch-topped granaries. Dogon women crouch in the tiny, beehive-shaped menstruation huts in order to protect the village from the devilry of their periods. I imagine being one of them, stuck in the hot huts once a month, banished and accursed for being female. Assou instructs me to carefully follow the path that he takes so as to avoid stepping on some taboo spot of ground, calling forth the wrath of spirits. Little Dogon boys gape at me as we pass: this isn’t a village that ever sees tourists.

We climb the rocky slope to the huts perched above, searching for where Yatanu lives. Assou has never met this woman, but he says he’s heard about her: She’s at least 70 years old, is one of the Dogon’s most powerful and feared witches. When she was ten, her parents, witches themselves, cut open her left arm and put a scarab beetle into the biceps, sewing the skin back up. Presumably the beetle died, but a spirit named deguru remained, with whom she converses and obtains knowledge about people’s pasts and futures. She can also summon up the power of her beetle spirit in order to manifest particular events, so most Dogon people live in terror of her. It’s hard to get a consultation with her because she doesn’t like most of her visitors and sends them away, but I’ve brought along a village officer who’s related to her, hoping he’ll help the cause.

We stop at a mud hut, and the Dogon man walks inside. After a short moment, Yatanu appears before us: a toothless and wizened woman, breasts lying flat against her chest, a scrappy indigo pagne tied about her bony waist. She stands in the shadow of her hut, staring at me. Assou tells her that I’m here to ask for a consultation—will she grant me one?

She steps forward into the sunlight, sits on her haunches, and studies me. Smiling nervously, I look into her eyes, clouded with cataracts. She says something in Dogon to the village officer, who then translates to Assou, who translates to me: “She likes you.”

Sighs of relief all around.

I ask my question: “Will I be able to get to Timbuktu?”

She puckers her lips and nods as the question is translated. She places her left arm tightly against her chest and speaks to the muscle where the beetle spirit supposedly lives. All at once, the muscle leaps up and hops; a large object seems to strain and lurch beneath the skin. I’ve never seen such a thing, nor has Assou—our mouths drop open. The movements become so frantic that I find myself taking a step back.

Assou explains that Yatanu is doing me a big favor by allowing me to see her. Each consultation costs a Dogon witch days, weeks, even months of her life by way of payment to the spirits. And if that weren’t bad enough, every time she’s shown her clients’ futures, she’s also shown her own future, including her death.

Yatanu reports her findings: “You’ll get to Timbuktu.”

*

Back on the Niger, the days fill with the slow progression of one village after the next, one grove of palm trees after another to break up the monotony of sand and shore. I stay with different tribes: the Fulani, the Somono, the Bozo.

All of it takes me to Lake Débo, finally, and the crossing I’ve been dreading, just as Park dreaded it two centuries before. I see it as the most treacherous part of the journey, where all sight of land will be lost for an entire day. If a storm should catch me while I’m in the middle of it, overturn and separate me from my boat, I could drown.

I start the crossing in the early morning, hoping to beat the wind and storms that inevitably arrive at midday. It’s not long before the horizon shows only the meeting of sky and water, the waves sizeable and unruly. But perhaps there is something to be said for a Yatanu’s assistance, because there is no hint of a rising storm.

A river steamer passes me, so loaded with people and baggage that water nearly spills over its gunwales. The ship overshadows me like a leviathan, her crew cheering and howling, the passengers craning to get a look at me in my tiny boat as I paddle feverishly beside their swift vessel. I follow the distant white buoys that guide the boats across, reaching one and then the next, hoping to catch sight of land. The heat becomes intense; my thermometer reads 106 degrees. But I don’t stop. The secret is to keep paddling, no matter what.

Finally, after seven hours, I’m relieved to see land and the broad channel of the Niger ahead. Hippos peer at me from the shallows, raising and lowering their heads, blowing air from their nostrils. Lake Débo, the part of the trip I’d been most worried about, barely stirs behind me.

*

The days become frustrating. I constantly fight this river as it curves and twists seem to take me nowhere. I call it “uphill paddling,” the battle against winds that kick up waves and batter me against the high clay banks. But at least my body cooperates, muscles appearing on my arms that I didn’t know I have, compensating for my injury.

Night arrives after yet another day of difficult paddling, and I approach a prosperous-looking village to try to buy a meal and lodging. Stopping at villages is always a crapshoot. What tribe will I get? Will they have food to sell me? Will they like me?

I’m greeted by the usual crowd. Kids swarm around me, yelling excitedly. They tell me this village is called Berakousi and that it sits at the spot where the Koula River enters the Niger. I ask what people they are and am told they’re Bozo. Fishermen.

As I search for the chief, it quickly becomes evident that I’m not wanted here. I’m particularly troubled by some young men, one sporting a black T-shirt with Osama bin Laden’s face printed on it like a rock star’s. They harass me in broken French. Where’s my husband? Would I like to have sex with them? What man back home allowed me to travel here by myself? Their faces are covered with indigo head-wraps, in the manner of North African Tuaregs, just their eyes peering out at me. Obviously, it’s cool to look Tuareg here. I ignore them, but I’m nearly knocked off my feet by the crowd of pushy onlookers. I’ve noticed a fine line between curiosity and aggression toward outsiders along the Niger, and Berakousi village clearly leans toward the latter. I don’t want to stay here. But food is important, and so I need to find the chief.

He’s out in the fields, so I sit on a wicker chair to wait for him. I refuse numerous requests from women who keep trying to pass me their babies, wanting me to breast-feed them. I wait and wait. The sun is almost gone. It’s too late to go elsewhere, the river too choppy and mercurial along this stretch to make night paddling safe.

The villagers are still milling about me when the chief appears, an old man named Gardja Jemai. He walks over and surveys me, frowning. I give him a wad of money as cadeau, explain as best I can that I’d like to buy a meal if possible and sleep on a patch of ground nearby. He stands there, frowning, saying nothing. I pass money to the best French speaker in the crowd and ask him to translate my request. There is a brief transaction and I’m told to wait. The young men sit around me, demanding money, too. One tells me that he wants the watch and flashlight that I’ve just removed from my backpack. He picks up these things and fingers them. Meanwhile, I seem to be the subject of a large, heated conversation among the villagers, of which I can understand only the word toubabou—whitey.

One of the chief’s four wives announces that she has food for me. I thank her and give her some money, and she drops a bowl in front of me. Inside is a rotting fish head, blooms of fungus growing on its skin.

“Mangez,” the woman says. She puts her fingers to her lips.

And I’m so hungry and fatigued that I do: I crack open the mottled skin and pull out bits of white meat. Everyone laughs heartily, and I see that this is a joke, feeding me a dog’s dinner. When I finish, I notice that Osama and company have requisitioned one of my pens. I decide to let it go. The young men nudge me. One sits close to me, his face inches from mine, and speaks threateningly through his Tuareg face wrapping. The chief—my usual benefactor elsewhere—stands by and does nothing. When the man wraps his hand around my wrist, I wrench my arm away, holding up a fist.

“Don’t touch me,” I say.

The villagers laugh. Scolding myself for my loss of temper, I get up, put on my backpack, and head to the river. Can I still get out of here tonight? But it’s darkness all around, the Niger churning madly at its confluence with the Koula. I’m stuck. Nothing to be done.

I sit for hours on the dark shore, slapping mosquitoes, hoping that the villagers will get bored and go back to their huts. It feels like a true Mungo Park moment: “I felt myself as if left lonely and friendless amidst the wilds of Africa,” he wrote in one of his last letters. When I finally return, the village has cleared out. One of the chief’s wives smiles in pity and brings out a foam mattress for me to sleep on. I lie down and wrap myself in my tent’s rain fly, my clothes becoming soaked with sweat. I shut my eyes to wait for first light, when I’ll leave this place. It is one of those nights that I know I must simply get through, that promises no sleep.

*

For the first time, it feels like Timbuktu is getting close. Perhaps it’s the sight of large dunes bordering the river, or maybe it’s the growing heat each day, rising well over 100 degrees. I no longer see the greenery that I had at the start of my trip. Almost imperceptibly, the desert country has arrived, each mile revealing an altering landscape that becomes drier, more thirsty for the waters of the Niger.

I keep marveling at how I’ve been paddling alone for weeks already. No one with whom to converse, to help me pass the time. No major diversions until the very end of each day, when I pull over at the nearest village, not knowing what to expect or what’s going to happen to me. Before I left on my trip, the idea of paddling alone on this river for so long had seemed daunting, but I’ve grown used to it now. The West, with its rushing and stress, had trained me to believe that I must try to fill every moment of every day with the accomplishment of something tangible and “important.” But here on the Niger, there is only the moment to moment paddling, life freely manifesting itself, showing me what it thinks should matter.

I pass the town of Niafounké, the Niger opening into a straightaway that ripples from heat waves, looking more and more interminable. I paddle through what appears to be a kind of marshland, passing small, dark brown objects barely resting on the surface of the water—what I take to be the omnipresent fishermen’s floats. I think nothing of them until one rises and spurts out air, two eyes peering at me: hippo! Hippos everywhere—I’ve never seen so many in one place. A whole hippo colony, and I’m stuck in the middle of it.

All I know about hippos is what I’ve gleaned from PBS shows, that they’re cute but bad-tempered critters, whose skin produces a natural sun screen. Hippos are often considered more dangerous than lions, more vicious than crocodiles, readily protecting their young to the death. And now I see baby hippos.

“Nice hippos,” I say to them. “Good hippos.”

The hippos just watch me. My rubber boat would be no match for their teeth, yet they seem lazy enough, a mother and baby lounging nearby. I slowly, cautiously turn my kayak around before breaking into panicked paddling. I rush upstream to the other branch of the Niger, feeling as if I’m going through a mine field. Hippo heads rise as I pass, making sounds like whales as they shoot air from their nostrils. The dark eyes watch me from just above the surface of the water, assessing, granting me passage.

*

Each day the land along the shore seems to get drier, more forbidding. Trees have all but vanished, and only scant brush dots the horizon. Still, given the starkness of the country, the people—of the Songhai tribe now—live in increasingly refined adobe dwellings that show a level of artistic achievement I haven’t yet seen along the Niger: doorways and window frames ornately carved, mosques exhibiting lavishly painted walls and expertly sculpted minarets.

I spend a night in a small village of adobe huts named Nakri, waking up with the rooster calls, day only a gray suggestion to the east. My stomach lurches, my guts feeling as if they’re being twisted. I can barely make it out of my tent and through the village to the Niger, where I vomit up bile. I kneel and hold my head. Only two days to my goal, and now this.

Some kind of dysentery, probably, though I can’t say which—amoebic, bacillary? I’m hoping it’s the latter, which is easier to cure. Still, when I return to my tent to take antibiotics, I immediately throw them up. A group of village folk have risen, and they watch me, tsk-ing. Poor, sick white woman. The children stare, silent and uncomprehending. All I can think about is reaching my goal, where I can stop finally and lie down, not having to do anything anymore.

I wash off my face, smooth down my T-shirt. I’m getting to Timbuktu if I have to crawl.

The women are still tsk-ing as I take down my tent and load up my kayak. Hunched over, I get in my kayak and wave goodbye, paddling off toward the morning sun appearing from behind some clouds.

I travel slowly through the intense, rising heat. When I feel too faint, I stop for a while, letting the current take me. But it’s a sluggish current and virtually no help. I try taking some more antibiotics, knowing they would help cure me if I could keep the pills down, but I quickly throw them up. I alternate between vomiting and paddling; my thermometer already registers 110 degrees. It is the hottest, most forbidding stretch of the Niger to date, great white dunes swelling on either side of the river, pulsing with heat waves. The sun burns in a cloudless sky that offers no hint of a breeze. Strangely, the shores here are more populated than ever, desolate adobe huts regularly breaking the monotony of desert. The luckier villages have a single scraggily tree to provide shade, its branches hanging despondently. I use these tiny villages as my signposts, reaching one and then the next, amazed by the tenacity of the Niger as it cuts through the Sahara, a gloriously stubborn and incongruous river.

I wonder what Park felt on this stretch. We can never know for sure, having no written record and only unreliable hearsay from his guide, Amadi Foutama, the lone survivor of the expedition, who claimed that Park and his men had to shoot their way through these waters. Everyone, apparently, wanted Park dead out here.

Which might explain why, at every turn, entire villages gather onshore to yell at me. I stick to the very middle of the Niger now and carry my can of mace in my lap, paddling as hard as my strength allows. Gone are the waves of greeting and friendship that I experienced at the beginning of my trip. Inexplicably, the entire tone of this country has changed.

*

One more day. If I can paddle about 35 miles, I can get to Timbuktu by night, but it’s

quite a distance on a river so sluggish, with my body so weak. I was awake most of the night from the pain and discomfort of the dysentery, though this morning I managed to keep down some antibiotics.

I start at first light. I have no food left, so I don’t eat. Even at eight in the morning, my thermometer reads over 100 degrees, great dunes meeting the river on either side, adobe villages half-buried beneath them. I am now in the land of the Tuareg and Moor, fierce nomadic peoples who crouch down close to the water and stare at me from their indigo wrappings, none of them returning my friendly waves. Park admitted fearing these people most, plagued by nightmares of his brutal captivity among them—nightmares that would follow him long after he escaped and returned to England.

I share Park’s trepidation, especially when an island splits the Niger, creating two narrow channels on either side. The narrower the river, the more vulnerable I am. Village people can reach me easier. There is less opportunity for escape. And this is the most populated stretch of the river to date, sizeable villages dotting the shore. All I can do is paddle hard, the villagers screaming and scolding me as I pass, some swimming after me. I have no way of knowing what their intentions are, so I follow my new guideline: Don’t get out of the boat—for anything.

When I stop to drink some water, a group of men leap into their canoes and come after me, demanding money. With a can of Mace in my lap, I manage to out-paddle them, but more canoes start to follow their example. It’s like a macabre game of tag, and while I can usually see them coming and get a lead, one man is able to reach me and hit my kayak with the bow of his canoe. I know one of us will have to give up, so I pace my strokes as if the pursuit were a long-distance race, and he soon falls behind.

It is more of the same at the next village, and at the next one after that, so that the mere sight of canoes onshore gives me fright. No time to drink water now—to stop is give them an incentive to come after me. Head aching, I round a bend of the Niger, the sun getting hotter and hotter. The river widens, and I don’t see any villages nearby. I stop paddling and float in the middle of the river, nauseous and faint, my thermometer reading 112 degrees. The current is so sluggish that algae grows on the surface of the water. I squint at the Niger trailing off into distant heat waves, the sands trying to swallow it. Reminds me of when Park once asked a local man where the Niger was headed. The reply: “To the end of the world.”

“This river will never end,” I say over and over. Still, I must be close. My map—not a very accurate one—predicts a shift to the northeast that signals the approach to Timbuktu, but that turn hasn’t come, may never come at all. But I’m determined to get to Timbuktu’s port of Korioumé by nightfall. I shed the protection of my long-sleeved shirt, pull the kayak’s thigh straps tighter, and prepare for the hardest bout of paddling yet.

I begin to paddle like a person possessed, the hours passing. The sun falls, burning dark orange in the west, and I see a distant square concrete building. Hardly a tower of gold, hardly an El Dorado, but I’ll take it. I paddle straight toward it, ignoring the pains in my body, my raging headache. Timbuktu, Timbuktu! Some Bozo fishermen stare at me as I pass. Strangely, they don’t ask for money or cadeau, yelling instead, “Ça va, Madame?” Are you okay? One man stands and raises his hands in a cheer, urging me on.

I round a sharp curve and approach Timbuktu’s port of Korioumé. I pull up beside a great white river steamer named, appropriately, the Tombouctou. All at once, I understand that there’s no more paddling to be done. I’ve made it. I can stop now. The familiar throng gathers in the darkness. Slowly I haul my kayak from the river, dropping it onshore for the last time.

People ask where I came from, and I tell them Old Ségou. They can’t seem to believe it. I unload my things to the clamor of their questions, but even speaking seems to pain me. Such a long time getting here—a month on the river. And was it worth it? Or is it blasphemy to ask that now? I can barely walk; I have a high fever. I haven’t eaten anything for more than a day. How do you know if any journey is worth it? I would give a great deal right now for silence. For stillness.

We will never know if Mungo Park reached Timbuktu. According to his guide, he was repelled by the locals. According to another account told to Heinrich Barth, a German explorer who visited Timbuktu years later, Park had actually landed near the city, only to be chased away by Tuaregs. In a final account told to British explorer Hugh Clapperton in 1827, Park made it to his golden city and was received warmly by the prince. Regardless, Park ended up dying on the Niger as he had prophesied, getting as far as Bussa, in modern-day New Bussa, Nigeria, before he disappeared. Drowned? Killed by natives? We’ll never know. The Lander brothers, British explorers who visited Bussa in 1830 in an attempt to resolve questions about Park’s fate, recovered from locals only his hymn book and a nautical almanac. Inside the almanac they found some of Park’s old papers—a tailor’s bill and an invitation dated November 9, 1804, that read, “Mr. and Mrs. Watson would like to have the pleasure of Mr. Park’s company at dinner on Tuesday next, at half-past five o’clock. An answer is requested.” The great Mungo Park, survived by a dinner invitation.

In the end, I suppose it doesn’t really matter what happened to Park. For him, as for me, the journey itself must be enough.

*

Timbuktu.

It is the world’s greatest anti-climax. Hard to believe that this spread of uninspiring adobe houses, this slapdash latticework of garbage-strewn streets and crumbling dwellings, was once the height of worldly sophistication and knowledge. The “gateway to the Sahara,” the “pearl of the desert,” the “African El Dorado” is nothing now but a haggard outpost in a plain of scrub brush and sand. After having had such a long and difficult journey to get here, I feel like I’m the butt of a great joke.

I walk the dusty streets. It is 115 degrees already and barely noon. I bow under the weight of the sun, and every action feels unusually ponderous. I pass wasted-looking donkeys scavenging in rubbish heaps and dodge streams of fetid wastewater trailing down alleyways. I visit the former homes of Scottish explorer Gordon Laing and Frenchman René Caillié, both of whom risked their lives to get here. They must have been just as disappointed. Caillié, the first European to reach Timbuktu, in 1823, and return alive to report on it, wrote that the city and its landscape “present the most monotonous and barren scene I have ever beheld.” But I like best what Tennyson said, who had tried to imagine the golden city in his poem “Timbuctoo” before any Westerners had gotten there:

“…your brilliant towers

Shall… shrink and shiver into huts,

Black specks amid a waste of dreary sand,

Low-built, mud-wall’d, barbarian settlements.”

Tourists, mostly flown in on package tours, wilt in the sun as they trudge through the streets, searching for whatever it is that Timbuktu had promised them. I imagine they, too, are disappointed, though this end of the world knows enough to sell them air-conditioned rooms and faux Tuareg wear at inflated prices. I see that Timbuktu is better left to name and fancy. It is not meant to be found.

History still pervades the place, with slavery one of its most secretive and enduring institutions. It occurs among the Bella, a people who are the traditional slaves of the Tuareg. If you mention the idea of slavery in Mali to some experts, though, they’ll be quick to cite the 1971 constitutional law that supposedly abolished it, insisting that the Bella are now paid workers with civil rights, including freedom of movement. In short, they’re not “slaves” anymore.

Others in Timbuktu tell a completely different story: that the Bella are slaves in fact, if not by law. They are still a form of property that the Tuareg refuse to give up; the Bella are often raped or beaten by their masters and are forced to turn over any money they earn. So is it slavery, then, or is it not?

Before my trip, I was perplexed by a recent human rights bulletin posted on the website of the U.S. State Department. It included reports of de facto slavery in Mali. Why had an entire group of people remained the equivalent of slaves in a country that claims slavery no longer exists? Was there no recourse for them? I mulled over the feasibility of actually freeing someone—not without its own degree of controversy. Some people familiar with the region assert that it’s not possible, that I would only be duped by those involved in the negotiations. Others argued that, at least on a psychological and economic level, the Bella would remain hopelessly tied to their Tuareg masters, so that anyone I freed would be left without a means to make a living at all.

But suppose I really could free someone? Just suppose. And then, what if I gave that person plenty of money to start up a business and become self-sufficient? Wouldn’t it be preferable to a dehumanizing, often brutal life of servitude? After much soul-searching, I finally concluded that it was worth a try.

My understanding about the situation in Timbuktu is that many of the Tuareg would release their Bella from servitude if someone would simply compensate them for officially letting them go. So I pay Assou’s travel expenses to come up from Mopti and help me with such negotiations, since he grew up in Timbuktu and knows the right people. He won’t accept any payment for his assistance: He wants to free someone as badly as I do. Assou is fond of saying that “what you do for others, you do for yourself.” Back in Mopti, he told me a secret—though he’s Songhai by birth, he was breast-fed by his mother’s Bella friend. “The Bella are in my blood,” he said. “I am one of them.” It is a daring admission for him to make, aligning himself with this outcast group: Some Malians use the word “Bella” as an insult.

*

And now a breakthrough: Assou has found a Tuareg master, Iba Zengi (not his real name, we’re told), who is willing to sell a Bella or two. Assou and I work to ensure the legitimacy of this arrangement, though everything must be done in secret, because slavery doesn’t officially exist in Mali. Assou will pass on my money to Zengi and pretend to be the one in charge of the negotiations, or none of this can happen. He told Zengi that he’s freeing the women as part of his college research, and that I’m coming along to help him take notes. Assou has not let on that I’m a writer, or that any of this is my idea.

Assou and I arrive at the Bella village, where we sit in the midst of small thatched huts. The people gather around—old and young, children half-clothed, women cradling infants. Assou admits he doesn’t know which Bella Zengi will choose to sell. I study each of them, trying to imagine what it is like to be them. To wake up each day, knowing you are owned by another, unable to marry without the master’s permission or to earn your own money.

There is a brief wait. Zengi lives elsewhere, among his own people; the Bela here report each day to him and his family for their work duties. A car arrives, and Zengi steps out. He is cloaked in indigo wrappings, the Tuareg man’s traditional desert clothing. I can see only his eyes as he daintily holds the bluish material over his nose and mouth, as if afraid of catching a cold. He sits on a mat before “his Bella,” as he calls them. He strokes and pats an older man as one might a favorite pet.

I have Assou ask if these are his slaves.

“Slavery is illegal in Mali,” he says calmly.

“But they are ‘your Bella.’ Are they paid monthly wages?” I ask.

He answers that he gives them a place to live, animals to raise, the clothes on their back. When one of them gets married, he provides animals for the bride price. This, I’m to understand, is their “pay.”

I turn to a middle-aged woman sitting nearby. “If she wanted to leave here and not come back, could she?” I ask him.

As Assou translates my question, Zengi’s veil falls for a moment, revealing a trace of a smirk. “Either I kill her, or she kills me,” he says. That is to say, Over my dead body.

I ask Assou to find out who is to be freed and whether my money is sufficient for the purchase of one or two people. They talk for a while. Zengi will free two women, household helpers whom he can spare, since he has three others and enough Bella babies to fill future vacancies. Their price is to be considered a bargain and a sign of Zengi’s beneficence: the equivalent of $260, more than the average Malian household income for one year.

He motions to a couple of young women standing at the edge of the crowd. They approach us with apprehension. “These are the women,” Zengi says. He orders them to take a seat on the mat before me. Once of them, I notice, holds a sickly looking baby girl. Their names are Fadimata and Akina.

“She has a baby,” I tell Assou. “Ask him if he can include the baby with her mother.”

A brief discussion ensues. “He won’t,” Assou says.

“Then ask him how much the baby is.” I can’t believe such a sentence has come out of my mouth, but Assou is asking him now and Zengi is sitting up regally, shaking his head.

“He won’t sell the baby,” Assou says. He leans closer to me. “He’s already giving us a favor by selling two people. It’s best, when a person gives you a favor, not to ask for more.”

Which I take to be a warning. I stare at the little girl, wondering what will become of her, but there is nothing to be done. While I know that her mother can still live in this village and will not be physically separated from her child, the girl will remain bound to a life of servitude for Zengi’s family as soon as she is big enough to work. A numbness comes over me. Better not to feel anything. I stand up and tell Assou that I’d like to get this over with. Pay Zengi his money. Buy these people already.

Zengi follows us behind a nearby hut—he doesn’t want “his Bella” to see him receiving money for their family members. Assou hands him the bundle of bills. The man pockets it and leads me back to the crowd. With a lavish wave of his hand, he directs the two women toward Assou and me.

“Go with them,” he tells them. “You belong to them now.”

And the shocked looks on their faces are hardly what I expected. Hell, I don’t know what I expected, but definitely not this. The two women obediently follow us as we walk away from the throng. I have no idea what to say to them, and ask Assou to tell them that I did this—bought them—so that they’d be free, earn wages, live without having to bow down to anyone.

The women just stand in front of me. Fadimata is smiling, who has the sickly baby, is smiling, but the other, Akina, looks like someone has just smacked her in the face. I hand them each a gold coin I brought from home as well as some Malian money. I have Assou tell them that this was all my idea, that this money is meant to help them start a business, get a footing somehow.

The women nod. Fadimata thanks me, but Akina looks down, silent. I don’t understand what’s wrong, so I ask if we can go somewhere to be alone. We head into a hut and sit on the sandy floor. The women sneak glances at me; Fadimata holds her—or perhaps I should say, Zengi’s—baby.

“So will you start a business now?” I have Assou ask them.

Fadimata nods, says she’ll buy some millet or rice to sell in the market. Though she’ll probably stick around this village to be with her baby, she’ll be self-sufficient. Any money she makes from produce that she sells in the market will be hers. She won’t have to report to Zengi.

“Did you like working for Zengi?” I ask her.

“No,” she says immediately. “I want to live my own life and have my own business.”

“What do you think about your baby belonging to Zengi?”

“I have no choice,” she says. She caresses he daughter’s head.

When I ask Akina if she liked working for Zengi’s family, she shakes her head, refusing to look at me.

“Did they hurt you?” I ask.

Softly, she says that they beat her. Fadimata nods in agreement: They beat her, too.

I really don’t know how to ask the next question, but I feel I must. Did any of the Tuareg men ever take them… rape them?

The women are silent.

I have Assou tell them that they’re safe, that I’m not going to tell any of the Tuareg what they say, that I’m their friend.

“It didn’t happen to me,” Fadimata says. “But it happened to my friend. She told me.”

Akina nods in agreement, but she says nothing. I sense that the women are withholding something. Akina looks scared, and she fingers her dress, frowning.

I have Assou ask her if she’s OK, and she looks into my eyes for the first time. “I feel shame,” she says, “about what happened.”

“Shame?” I ask Assou.

And it comes out that she feels ashamed that she was sold like some animal. She’s ashamed to be sitting in front of me.

“No,” I say. “Tell her not to.” I reach over and take hold of her hand. She stares at me; we’ve got tears in our eyes. I keep squeezing her hand. “Tell her not to feel ashamed.”

Assou tells her, and it is as if a transformation has taken over her. Her whole countenance relaxes. When I ask her if she’d tell me how the Tuareg have hurt her, she stands and her hands come up and down with an imaginary stick, as if trying to drive it through someone’s body. Her expression is one of pure rage, pure hatred. Both women tell me that they’re beaten daily, for no reason whatsoever.

They explain to me that they must do absolutely everything for their Tuareg masters, and it is a description I’ve heard from other Malians—that the Tuareg consider themselves an aristocratic race, above everyday tasks.

I ask the women if they can move away now, go to Mopti if they wanted. I’m wondering what guarantee there is—if any—that Zengi won’t reclaim them the minute I leave.

“No, he can’t,” Fadimata says. Akina nods in agreement. “We have his promise. When he told us to go with you, that is a guarantee that means ‘You’re free.’”

I can only hope they’re right. In a society that refuses to acknowledge its slavery, there can be no official papers drawn up, no receipts. If Zengi is honorable, upholds his part of the bargain—as the women assure me he will—then they have nothing to worry about. And the fact that they are already planning their futures, telling me about the millet they will buy, is enough to reassure me. For now. At any rate, perhaps they won’t be beaten or humiliated anymore.

When I get up to leave, I shake their hands. They tell me that God will bless me, will take care of me for what I’ve done. I’m glad to see their happy expressions, though I don’t know what to say. Maybe Fadimata can buy her baby from Zengi if she makes enough money? I don’t have words.

*

I go with Assou to the Djinguereber mosque. I want to see the door that, if opened, can end the world (at least, according to local legend). This mosque, Mali’s oldest, was built by the great Songhai king Mansa Musa in the 14th century. It has survived the centuries virtually intact and now sits on the edge of town, its spiked adobe minarets reaching skyward, garbage swirling about its walls.

We have the mosque to ourselves, the caretaker busy with tourists on the roof. Inside it is dim and cool. Faint light trails down from skylights, exposing the clouds of dust kicked up by our feet. It is hugely empty here, the adobe walls revealing the pressing of ancient hands.

The special door is in a nondescript wall along the far side of the mosque, hidden behind

a simple thatched mat. Assou tells me that no one is shown the door anymore. He doesn’t know why. Perhaps it’s too dangerous.

“I want to see what it looks like,” I say.

Assou laughs nervously. “I never met someone as curious as you.”

“I’m serious.”

“Then go look.” But I notice that he, himself, is scared.

The empty mosque rings with our voices. Dust swirls in the shafts of light. Kittens lie in the shadows of columns, their ears flickering to the sounds of our voices.

I creep forward and gently pull back the mat. And here it is: the door that can end the world. It is made of wood, the middle part rotted away. It looks unremarkable, like a piece of faded driftwood. Suddenly, impulsively, I stick out a hand and touch it.

The world doesn’t quake. The waters don’t part. The earth continues on its axis, churning out immutable time.

“The world hasn’t ended,” I declare, my voice echoing off the far walls.

“You must open it,” Assou laughs.

And I could open it, standing here as I am, the caretaker blithely unaware on the roof of the mosque. For an insolent moment I pretend I hold the world in my hands. I think of Zengi and the slave women. I think of the Bozo fisherman cheering me on to Timbuktu. It is such a kind yet cruel world. Such a vulnerable world. I’m astounded by it all.

|

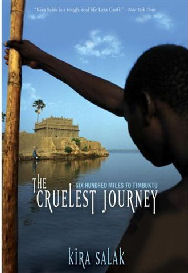

THE CRUELEST JOURNEY: SIX HUNDRED MILES TO TIMBUKTU

READ THE ENTIRE STORY OF SALAK'S JOURNEY UP THE NIGER RIVER THROUGH MALI

by Kira Salak

Kira Salak became the first person in the world to kayak alone 600 miles on the Niger River of Mali to Timbuktu, retracing the fatal journey of the great Scottish explorer Mungo Park. Enduring tropical storms, hippos, rapids, the unrelenting heat of the Sahara desert, and the mercurial moods of this notorious river, Kira Salak traveled solo through one of the most desolate and dangerous regions in Africa, where little had changed since Mungo Park was taken captive by Moors in 1797.

Dependent on locals for food and shelter each night, Salak stayed in remote mud-hut villages on the banks of the Niger, meeting Dogan sorceresses and tribes who alternately revered and reviled her--so remarkable was the sight of an unaccompanied white woman paddling all the way to Timbuktu. Indeed, on one harrowing stretch she barely escaped with her life from men chasing after her in canoes. Finally, weak with dysentery but triumphant, she arrived in the fabled city of Timbuktu and fulfilled her ultimate goal: buying the freedom of two Bella slave women. This unputdownable story is also a meditation on courage and self-mastery by a young adventuress without equal, whose writing is as thrilling as her life.

|

|

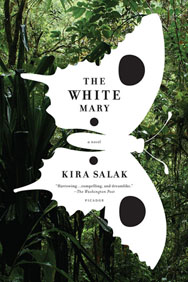

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()