TOTALITARIAN ADVENTURES IN BURMA

published in National Geographic

(in slightly different form) as "River of Spirits"

The motorboat came directly toward me, at full speed. For a minute I was in denial: I was sure it would veer to the side, pass me by. But its course remained dead-set on the front of my kayak. I paddled in a panic toward the left-hand shore, only to see that it had changed its direction, was coming straight at me. I could see the cloud of smoke from its engine, hear the deafening roar of its outboard. I couldn’t think of a single thing I could do to avoid the approaching tragedy. Adrenaline took over. There was no past or future, just each moment unleashing itself in excruciating present tense.

I became engulfed in diesel fumes. The boat’s engine stopped. A large wave flung me sideways, nearly capsizing me. As I struggled to right myself, I saw a couple of men in the boat, shouting violently at me.

“Where you go! Where you go!” one man yelled in poor English.

It took me a moment to orient myself. A boat. Men yelling at me.

“Where you go!” the man yelled with greater fury.

I knew they must be the police. Virtually no one else in Myanmar—a country largely populated by subsistence farmers, where the average family is lucky to make $300 a year—could afford a speedboat, let alone the gas to run it.

My body was still quaking from the near collision.

“You! Where you go!” the man said, more violently.

I felt myself lucky to be alive, uninjured. I waved my paddle high in the air to try to get the attention of my guide in his distant boat. Jiro, the 33-year-old translator working for the Ministry of Tourism, had copies of my passport and special permit allowing me to travel on the upper Irrawaddy River, an activity normally forbidden to tourists. There was a well-trodden tourist trail—from the capital Yangon to Mandalay to the ancient temples of Bagan—that was what most visitors to the country would ever see. It was not, however, my route. I had vowed to experience Myanmar by traveling all 1,350 miles of the Irrawaddy River, the country’s historical lifeline. This included kayaking the first 350 miles of the upper Irrawaddy—something no one had ever tried before.

Pre-trip, I had assumed I would be paddling alone, carrying all the food and gear I needed to camp and be self-supportive. But this had not been permitted. The government had required that I organize an expensive individual tour and hire a boat and entourage (composed of a guide, a cook, and an assistant) to accompany me as I kayaked. In particular, I needed a guide to act as minder—in this case, Jiro—who would drop off copies of my passport and permits at village police or military intelligence posts along the river, as well as file written reports about my daily activities.

It had not been how I envisioned experiencing life along the Irrawaddy River. Jiro knew this, felt bad about it. But there was nothing he could do. We struck a compromise: he would keep their boat far away from me, so I could paddle with the illusion of doing it alone. But already the innocence of my trip had taken on a political flavor that I could have never imagined: I was being constantly monitored by the Myanmar government.

I watched, with relief, as Jiro’s boat turned around and sped toward me. The policemen were still barking at me, enraged by my silence. The waters of the Irrawaddy surged by, threatening to carry us all off. I was in the middle of the First Defile, an extremely narrow, rocky, 35-mile-long channel full of scores of treacherous whirlpools and rapids. For the six months rainy season, no boats even dared to venture up this channel, the high-water mark on the cliffs an imposing 80 feet above me.

Thankfully, Jiro’s boat finally arrived.

“These men tried to run me over,” I said to him as he greeted me on the stern of the boat. His face twitched slightly. He stood a little more erect. The men in the boat began complaining to him in Burmese until he handed over a copy of the permit that allowed me to be on the river. As they looked it over, he turned on his joviality, joshing and cajoling them like a pro. Satisfied, they handed back the papers and sped off.

As soon as they were gone, Jiro turned to me. “We must put your kayak inside the boat,” he said gravely, like a warning.

“Why?”

“They don’t understand what you are doing.”

Wasn’t it self-evident? “I’m in a kayak,” I said. “I’m kayaking.”

“I know.” But he ordered his two assistants to hoist my boat from the water. “I’m sorry.”

*

Before I went to Burma—but I must be sure to call it Myanmar—I was given an edict: do not write anything negative about the country. This from a Burmese man who, for a hefty price in U.S. dollars cash, would arrange everything I needed in order to explore the country’s largest, greatest river, the Irrawaddy, for a National Geographic story. That was my first taste of the country, of its climate of fear, and I hadn’t even arrived yet.

See only what is positive.

Love Myanmar.

As an American, I wasn’t used to being told how I should view and write about a place. But my intention was positive. I hoped to love the country. I intended to explore the romance of a river which has piqued the imagination of some of the world’s greatest writers. Of course, I knew about Myanmar’s politics. I knew that it has a totalitarian form of government controlled by a posse of ruling generals; in late 2004 U.S. Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice listed Myanmar (once called Burma until, in 1989, the military junta made a unilateral decision to rename the country) one of the world’s six “outposts of tyranny.” It shares this unpleasant membership with North Korea, Iran, Zimbabwe, Belarus, and Cuba. Myanmar may be most well-known around the world for producing Aung San Suu Kyi, winner of the 1991 Nobel Peace Prize for her non-violent attempts to guide the country into democracy. In 1990, Suu Kyi’s National League of Democracy (NLD) won 80 percent of the seats in national elections; the ruling junta, refusing to relinquish power, ignored the election result, arrested Suu Kyi and her NLD leaders, and clamped down on all opposition groups. It was a move that made Myanmar exceedingly unpopular with Western nations, as did emerging human rights reports which cited evidence of massacres, torture, and the forced relocation of ethnic tribal communities by government troops.

Surely, it was this recent history that followed me along the Irrawaddy as I began my long journey to the sea, and that offered an explanation of why large swaths of the country were off-limits to tourists. Though I was doing nothing more than paddling, Jiro would come over, tie up my kayak, and pull me inside his boat whenever we approached a town. Any foreigner off the usual tourist route was regarded suspiciously, and he didn’t want to inflame the curiosity of people onshore.

Gratefully, the Irrawaddy River knew nothing about paranoia or politics. It was 1,350 miles of blithe indifference to such things. No matter what happened, I could always count on it carrying me along, as if the river were a metaphor for the Buddhist teaching: all that arises, passes away. The waters—still cold to the touch—spoke of glacial beginnings in the snow-covered peaks of the Himalayas below Tibet. They had surged through jungle-covered highlands to emerge in these sun-scorched plains of central Myanmar. And they would continue to the ocean, releasing finally into the Andaman Sea in the Bay of Bengal. Myanmar’s longest river, the Irrawaddy saw some of Asia’s greatest ancient kingdoms flourish along its banks—the Mon, the Pyu, the Shan. Later, it carried the Mongol hordes from China to ravage the Burman Empire’s golden city of Bagan in 1287, thrusting the region into centuries of conflict and decline. In 1885, the British traveled up its waters to annex Upper Burma into their colonial empire, only to use it for their longest military retreat in history before the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII. The Irrawaddy has seen it all.

*

I’ve always believed the best way to know a river is to paddle it, to feel its undercurrents and speed, to take in the changing nature of its banks. As I paddled, it was a delight to explore the romance of the river which stirred the imagination of writers like Kipling and Orwell. The name “Irrawaddy” is an English corruption of Ayerawaddy Myit, which some scholars translate as ;“river that brings blessings to the people.” But it’s less a river than a test of faith, receding during the country’s dry season until its banks sit exposed and cracking in the sun, only to return each spring with the monsoon, overrunning banks, flooding fields, replenishing the country with water, fish, and fertile soil. The Irrawaddy has never let the Burmese people down. It is where they wash, what they drink, how they travel. Inseparable from their spiritual life, it is their hope.

Not surprisingly, the river is inseparable from the country’s spiritual life. I visited a small, lavishly decorated bamboo shrine docked beside a village—the first of a handful of such shrines that I would see as I traveled the river. Inside, sitting on an altar, was a small bronze statue of a Buddhist monk, smiling and gazing heavenward: Shinupagoda, the saint of the Irrawaddy. He is the saint of boatsmen, of fishermen, of anyone who relies on the river. I hoped, too, that he was the saint of kayakers as I bowed before him, praying for a peaceful journey. Local villagers left offerings of flowers, rice cakes, locks of their hair at his altar. In another day or two, they would set the raft loose so it could float down the river again, bringing blessings to the next village that took it in. I wondered if the raft would ever make it to the termination of the river, nearly 1,000 miles away. I could hardly imagine that end for myself, the river opening wide, taking me into limitless blue waves.

After I left the First Defile and passed the town of Bhamo, each bend in the river, each rise of a hill promised the sight of a bright white pagoda pointing heavenward. I had entered Buddhist Burma, riverside temples smelling of sandalwood incense and tiaré flowers, bells on pagoda steeples tinkling seductively in the breeze. The river wound through the Second Defile, past pristine 800-foot-high cliffs, at the end of which sat one of the Irrawaddy’s most miraculous sites: Shwekyundaw—Golden Royal Island—where thousands of stupas rose from a tiny island barely half a mile long.

I paddled toward it with excitement, parking my kayak on a sandbar near white steps that rose from the water’s edge. Everything was strangely silent. No one was around; Jiro’s boat was busy docking itself in the distance. I could tell that this was a special place by the feel. That tingling yearning to enter it. To the Burmese people, the Golden Island is an unspeakably holy place, where the Lord Buddha himself is said to have pointed, announcing that an island would rise from the Irrawaddy. And not just any island, but a place most auspicious, where a sacred pagoda would be built along with 7,777 stupas, each to contain a relic from his own body after he died. And so Golden Island rose as prophesied, where over 2,500 years later the promised stupas still stand, crumbling in the heat and dust of millenia.

Jiro joined me. I walked slowly, reverentially up the long covered walkway that led to the central pagoda. I could imagine the devotion of eons there—all the entreaties sent heavenward, all the laments. “Life is suffering,” said the Buddha in his first Noble Truth. Ancient bronze and marble statues of his likeness lay strewn about the rubble. “All is impermanent,” he also taught, scores of temple antiquities resting like so much debris on the dusty pathways.

We reached the welcome shade of the monastery, an old man in saffron robes greeting us with a smile and bow. He was the head monk, the Venerable Bhaddanta Thawbita. At 82 years old, his face lined and burnished from years in the sun, he looked as much a relic of the ancient island as its crumbling stupas. He had lived on Golden Island his entire life, beneath its arching bodhi trees and golden pagoda. During WWII, he watched as Japanese soldiers hid among the stupas, forcing the Allied Forces to bomb the entire island. Miraculously, two buildings survived completely unscathed: the main temple and a crypt where four sacred statues—depicting the Buddha’s previous incarnations—were kept, each believed to contain actual blood.

They are considered such holy objects that, in 1997, General Khin Nyunt—now ousted from the ruling junta—decided he wanted to acquire the glory of moving them from the island to a special temple in the capital. Thawbita strongly cautioned him against it. “Move them if you can,” he said, “but if anything happens, it’s not my responsibility.” Nyunt ignored the warnings and sent a procession up the Irrawaddy. Witnesses later described what had happened: how the sky grew dark and a violent storm began at the moment that Nyunt reached the river with the statues. Terrified, the chastened general promptly returned them.

Given their special history, I wanted to see them all the more. Thawbita, busy with visiting locals, had his assistant monk, 67-year-old Ashin Kuthala, guide me into the heart of the temple. I expected the statues to be stored deep in a vault, far from visitors, but instead they rested on silk sheets inside a gilded cage just a few feet from passersby. Each had been so covered with gold leaf over the centuries that their original forms looked indistinct.

As a practicing Buddhist, I found their close proximity a rare gift. I gazed at the large padlock on the metal door, wondering if anyone was ever allowed inside.

“Do you ever open the door?” I asked Thala.

“Only for V.I.P.s,” he said. “For Prime Ministers, Heads of State.”

“Oh.” I studied the statues, disappointed. “But I’m V.I.P.!” I joked. “I’m National Geographic.”

Jiro translated this. We tried not to laugh. Thala took a moment for consideration, and—to my utter astonishment—went to get the keys.

He told me I wouldn’t be allowed to enter the chamber itself, so he asked me to sit on the floor just outside. Unlocking the door, he went inside and brought out one of the statues. Holding it, he asked me to pray. As I did, Thala placed the statue on top of my head and began a recitation in Pali. All at once the passing seconds felt indefinite. My eyes filled with tears. I was beyond time.

*

Over the next several days, I needed all of the courage and patience that I had prayed for. I began paddling through the Dry Zone of central Myanmar, which received little more than 25 inches of rain a year—enough to classify it as desert. The land had turned brown and parched, patches of cacti providing the landscape’s only respite of green. Each day, the sun’s heat reached at least 115 degrees, dust clouds blooming at the slightest suggestion of wind. My only shade was the four-inch brim of my hat.

I had never kayaked in such high temperatures. The sky of central Myanmar was a scathing white screen that sucked all color from the earth and left me exhausted and enervated within an hour. It seemed impossible to stay adequately hydrated. As I paddled, my head throbbed relentlessly from the heat, sweat saturating my clothes. I wore a long-sleeved shirt to protect myself from the sun, dousing it in river water to try to keep cool, but it was an act of futility—the sun quickly evaporated any water.

The Irrawaddy was at its lowest level of the year, and I passed through labyrinths of sandbars that acted as local villagers’ only arable land, covered with crops of corn, beans, and watermelons that would have to be harvested before the return of high waters in a month. As I clung to the security of the shoreline, streams of barges overloaded with old growth teak logs come at me like leviathans; it was a wonder there were any trees left. The river, passing numerous populous towns with no waste water treatment facilities, became covered for miles with raw sewage.

As I kayaked through floating trails of excrement, I was bolstered by the memory of a local woman named Than, 35, whom I met squatting on the rocky shore near the town of Myitkyina. Her wiry forearms were burnished a coffee brown from the sun, and she wore a dirty sarong around her tiny waist. All day long she raised a mallet over a pile of rocks before her, cracking them into halves, into fourths, to sell to the road builders. Her two-year-old son, naked and with a bloated belly, stood nearby, still too young to be of use; her two daughters, ages 3 and 12, helped to gather more rocks. I’d asked how long she’d been doing such work. “Ten years,” she said. There was no bitterness in her voice. No sorrow. Just the crack of her mallet on a new stone. We had barely begun speaking before a well-dressed, official-looking man arrived, watching us with hands on hips, chastising us with his stare. Than shrank into silence, and I wondered how I would ever get to know anyone in this country.

Since 1996 the Myanmar government has sponsored a campaign to encourage tourism, but there’s been much debate in the West about traveling to this country. Suu Kyi advises against it, arguing that tourism funds the government’s oppression; other Burmese exiles believe tourism creates much-needed jobs for local people and provides foreign witnesses to internal conditions. Shortly after I’d arrived in the country, I shared a taxi with a stranger in Yangon who suddenly started telling me about his support for Suu Kyi and his expectations of the collapse of the country’s military leadership. There seems to be a need among people to talk to someone—anyone—from outside the country. To tell the world about a hidden, deep suffering. Unwittingly, I find that I am viewed less as a tourist than as a witness.

As I paddled along, there was one thing to be grateful for: the regular visits by police in motorboats had begun tapering off, as I was getting near the tourist zone of Mandalay, where boats full of foreigners were the norm, everyone heading south to see the ruins of Bagan. Though Jiro still had to stop at local towns to report my presence, he was able to relax more, keeping his boat farther from me than ever. When I reached the tiny village of Myitkangyi, it was the first time I’d arrived somewhere before him, before villagers could be alerted or officials briefed. Finally, my trip felt spontaneous, authentic.

As I pulled my kayak onto shore beside a large teak vessel, a group of children gathered nearby, mouths agape. I took a step toward them, but they ran off, screaming in terror. Thinking it may have been my appearance—the bush hat and sunglasses, my face covered with a mask of white sunscreen—I removed as much of this as I could. A sole child remained, a boy of about three who, to judge from the fervent screams of his older brother hiding behind a nearby boat, obviously hadn’t the good sense to avoid strange white women arriving in inflatable kayaks. As soon as I turned my back, the brother leapt out and seized the child, dragging him to safety.

I took out a bag of candy from my backpack and held it out to the wary children. “I come in peace,” I said.

But only the encouragement of an approaching adult saw them creep toward me to snatch a piece of candy. Soon, every child in Myitkangyi who hadn’t yet risked his or her life to get a piece, appeared, and my bag was completely emptied.

As was the case in most Irrawaddy villages that I visited, Myitkangyi hadn’t any electricity or running water. No motorized vehicles. No telephones. No paved roads. Everyone lived in thatch huts on stilts, and the only means of transportation was ox carts. Most villages had to be self-sufficient, having their own blacksmith, carpenter, wheelwright. It was as if I’d gone centuries back in time.

I pitched my tent on a sandbank across from the village, adults wandering over to sit on their haunches and study me for hours. When I ate dinner in the boat, word went out. Soon, a large crowd of spectators had gathered, sighing in unison as I opened a can of Coke, exclaiming if I dropped something. The innocence of Myitkangyi touched me.

The local fishermen, however, were a bit more used to outsiders. Scientists had recently converged on the tiny village to witness Myitkangyi’s claim to fame: they are the only people in the world who cooperatively fish with river dolphins. To San Lwin, 42, a fisherman who came to show me the practice the following morning, there was nothing remarkable about this. His father had taught him to fish with the dolphins when he was 16; the practice had been passed down in his family for generations. Lwin’s face, bronzed and deeply creased from the sun, expressed a kind of reverence as he studied the smooth silver waters for sight of a dolphin fin. In the placidity of his stare, in the calm, steady strokes of his paddling, it was as if fishing with the dolphins was not just his livelihood, but his religion.

“If a dolphin dies,” he told me, “it’s like my own mother has died.”

Two other canoes followed ours, one carrying a nervous Jiro who, unable to swim, huddled in my kayak’s lifejacket. We headed toward an area of river where the trained “pod” of dolphins, numbering no more than 20 individuals, could usually be found. In total, there are no more than 72 Irrawaddy dolphins in all 1,350 miles of the river that gives them their name. Classified as “critically endangered” by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the animals maintain a tenuous existence in isolated spots of the Irrawaddy cut off from the noise of gold mining machinery or heavy ship traffic. Still, they can’t wholly escape two of their biggest threats: electric and gillnet fishing. As the former is illegal in Myanmar, it usually takes place after dark, fishermen shooting high volts of electricity into the water to stun fish—and any dolphins that happen to be nearby. Arguably the biggest threat, however, is gillnet fishing, men stretching long nets across sections of the river to catch anything and everything passing by.

We reached the area of river where Lwin said the dolphins liked to congregate. Though I saw nothing breaking the surface of the water, Lwin was unconcerned. He and the other fishermen began tapping small, pointed sticks against the side of their canoes and making high-pitched cru-cru sounds. “We are telling the dolphins that we are here,” Lwin explained to me.

In a few moments, a single dorsal fin rose from the river. Suddenly, several gray forms arched through the water toward us, their slick bodies gleaming in the sunlight. One, with a small calf by her side, spit air loudly through her blowhole.

“Goa Htit Ma!” Lwin yelled, pointing at her and smiling. “She is calling to us!” Goa Htit Ma had been fishing with them for at least 30 years old, Lwin said; they could distinguish her by a unique mark in her fin.

The fishermen splashed their paddles to tell the dolphins that they’d like to fish together. One dolphin separated from the group and began swimming back and forth in large semicircles.

“He’s finding fish for us,” Lwin explained. “It’s one dolphin at a time. They like to take turns.”

As did the fishermen, with Lwin first in line. He stood poised on the bow of his canoe, net in hand, studying the water with the intensity of a pitcher before a throw. The dolphin submerged again, reappearing less than 10 feet from our canoe, its tail frantically waving. Lwin wound up like a discus thrower and tossed the heavy, lead-weighted net over the spot where the dolphin had shown its tail. The net spread in the air like a great parachute, quickly sinking beneath the water. As Lwin slowly pulled it in, numerous silver fish flapped in the strings. Though it seemed as if the dolphins unselfishly assisted the humans, Lwin told me that they helped themselves to any fish escaping the nets.

The next fisherman in our group began tapping his stick and calling to the dolphins. A new animal responded with a splash of its tail. This symbiotic relationship between dolphin and human, intricately choreographed over untold generations, stunned me with its beauty.

“The dolphins really like doing this,” I said. “Don’t they?”

“They love it,” Lwin said. He told me that sometimes, when he goes night fishing and falls asleep in his boat, they will come and spit water on him to wake him up, so they can fish together.

After several turns of fishing, one of the dolphins let loose a deep sigh through its blowhole and the entire group disappeared beneath the water.

“They want to take a break for a while,” Lwin said.

And so did we humans, parking our canoes on the shore to eat lunch. Nearly two hours later, a dolphin fin re-emerged from the water, followed by the sight of several slick bodies. We hurried back to the canoes to follow them upriver. Along the way, we passed some gillnet fishermen camped along the shore, the dolphins giving their nets a wide berth.

The men called to us. “Do you want to see a big fish?” they asked. They pulled a thick rope from the water, at the end of which, attached through mouth and gill, was a six-foot-long nga maung, or catfish. Its head alone was a foot and a half wide, its great whiskers three feet long. Its orange and pale white body, dotted with black spots, glowed in the sunlight, a brilliant masterpiece of creation. Tomorrow, they would take it to Mandalay and sell it at the market. It would net them a small fortune: 45,000 kyat, or 55 dollars—nearly one-third of the average Burmese’s yearly income.

Goa Htit Ma and the other dolphins began to swim away, careening through the water and leaping playfully, calling to us through their blowholes. Just as we began paddling after them, I asked Lwin to wait.

“I’d like to buy the catfish first,” I said.

The gill-net men laughed heartily at the idea, but when I showed them the 45,000 kyat, they handed over the fish. It struggled violently in the water, nearly capsizing our narrow canoe, and I hoped that we could get safely across the Irrawaddy with him. I wanted to reach the deep channel on the opposite bank to set him free. For centuries, Buddhist monks living along the river had cherished these giant catfish; at the monastery of Thabbeikan, on an island in the Irrawaddy’s Third Defile, monks told me that they hand-feed giant catfish during the rainy season. And now Lwin, a Buddhist, eagerly embraced my plan to free the fish, noting the charity of my act and the karmic merit I would accrue for myself. But I had never thought of that; I just didn’t want that great orange fellow to die. When we finally reached the deep section, far from any of the gillnets, Lwin carefully untied the rope. Speaking gently to the struggling fish as if to a small child, he suddenly yanked the rope from its gills and it sped off into the deep. Behind us, I heard a noise: Goa Htit Ma and the other dolphins had followed us, far from their nook of habitat in the distant channel. It was as if they knew, somehow, that we were freeing their brethren of the river, and they had come along to help.

*

Mandalay. My kayaking of the Upper Irrawaddy was over. Already I was obsessing about the simple pleasures of air-conditioning and a shower. It’d been weeks since I’d experienced either. As Myanmar’s second largest city, Mandalay met the mud banks with a spectacle of crowds, diesel exhaust, and big town urgency. A high hill rose above the city, covered with gold-covered pagodas that gleamed magically in the late afternoon sun.

Jiro rented a tourist boat for us with a covered upper deck and—most spectacular to me—a toilet. After weeks of paddling a kayak 25 to 30 miles a day in full sun, I felt wonderfully spoiled. We made fast time now. Shortly after the Chindwin River merged with the Irrawaddy, doubling its size, we reached Myanmar’s greatest tourist attraction: the temples of Bagan. There, on the shores of the river rose more than 4,000 ancient, abandoned monuments, occupying a mere 20 square miles. The obsessive building began in 849 A.D., only to cease abruptly in 1287, when Kublai Khan’s Mongol army sacked the golden city. Bagan was the first place I visited along the river where my foreign presence came as no surprise to anyone.

Further down river, past the oil fields of Yenan-Gaung and the old city of Pyay, we stopped near a small village called Thar Yar Gone that was having a nat-pwe, or spirit festival. We headed there in an ox cart in the debilitating heat of midday, the animals kicking up brown dust that settled on my skin like soot. I could tell from the growing noise that we were getting close to the festivities. Drums and gongs sounded, an oboe wailed, and a voice sang out a high-pitched tune that shattered the heavy heat of the afternoon. We passed through a run-down village, coming to a jolting stop before a large thatch hut. The owner invited us inside, where musicians played loud, frenetic music before a crowd of rowdy on-lookers. On the opposite end of the hut, on a raised stage, sat several wooden statues: nat, or spirit, effigies.

The Cult of the Nats is Myanmar’s ancient animist religion. In the 11th century, Burmese King Anawrahta declared that the Theravada sect of Buddhism would be the country’s official religion, denouncing nat worship as a form of occultism forbidden by Buddhist scriptures. But when his attempts to eliminate it proved fruitless, he regulated it instead, establishing an official pantheon of 37 spirits to be worshipped as subordinates of the Buddha. The result is that—well into the present-day—all Buddhist temples in the country have their own nat-sin, or spirit house, attached to the main pagoda.

Though people still worship spirits outside the official pantheon, the 37 enjoy a kind of V.I.P. status, with traveling troupes of dancers, singers, and musicians reenacting the stories of the spirits’ tumultuous human lives and shockingly violent deaths. Each performer is called a nat-kadaw, literally “spirit’s wife”—a role that lies somewhere between psychic and shaman. For nat-kadaws are more than just actors; they believe that the spirits actually enter and possess them. Each had an entirely different personality, requiring a change in costume, decorations, and props. Some of the spirits might be female, for whom he would don women’s clothing; others, warriors or kings, required uniforms and weapons.

I passed through the large crowd, stepped beneath the stage, where a lavishly beautiful woman introduced herself as Phyo Thet Pine. Only she wasn’t a woman—she was a he, a transvestite, wearing bright red lipstick, expertly applied black eyeliner, and delicate puffs of powder on each cheek. I saw myself in her—his—mirror, smears of dirt covering my sweaty arms and face, and felt overwhelmingly self-conscious before his painstakingly created femininity.

There were several other men as well, dressed gorgeously as women, who gazed upon me with curiosity. I smoothed down my hair, smiled in apology at my appearance. Pine explained that he was the head nat-kadaw, and I shook his delicate, well-manicured hand.

To the Burmese, being born female rather than male is karmic punishment indicating grave transgressions in former lifetimes. Many Burmese women, when leaving offerings at temples, pray to be reincarnated as a man. But to be born gay—that is viewed as the lowest form of human incarnation. Where this must leave Myanmar’s gay men, psychologically, I could only imagine. It perhaps explains why so many, like those in Pine’s troupe, become nat-kadaws. It allows them to assume a position of power and prestige in a society that would otherwise scorn them.

Pine, who was the head of his troupe, conveyed a kind of regal confidence. His trunks, full of make-up and colorful costumes, made the small space look like a movie star’s dressing room.

“Did you always want to be a nat-kadaw?” I asked Pine.

He finished carefully outlining his eye with eyeliner before responding. “My heart was open to the spirits ever since I was young, and they easily entered me.”

He became an official “spirit’s wife,” he said, when he was only 15. He spent his teenage years traveling around villages, performing. But Pine dreamed of becoming an expert nat-kadaw. He went to Yangon’s School of Culture, learning each of the dances of the 37 spirits, which, because they differed from typical Burmese dance, meant acquiring special skills. He also mastered the spirits’ songs from the ancient text, Mahagita Medanikyan, or “Odes to Nats.” It took him 20 years to learn his craft. Now, at age 33, he commanded his own troupe and made 110 dollars in kyat per two-day festival—a small fortune by Burmese standards.

“Right now,” I asked him, “is there a spirit inside of you?”

He glanced at me and smiled patiently. “Not yet.” He drew an intricate mustache on his upper lip. “I’m preparing for Go Gyi Gyo.”

Who was the notorious gambling, drinking, fornicating spirit.

“Are you scared of any of the spirits who enter you?” I asked him.

Again, the smile. “No.”

It was time for Pine to perform. Jiro and I stepped from beneath the stage, a man ushering us to a seat of honor before the performance area. The crowd, well juiced up on grain alcohol, hooted and shouted for Go Gyi Go to show himself. A male nat-kadaw in a tight green dress began serenading the spirit: “Everybody likes you, Go Gyi Gyo. You’re such a friendly man, so unselfish.” The musicians created a crescendoing cacophony of sound. All at once, from beneath a corner of the stage, a wily-looking man with a mustache burst out, wearing a white silk shirt and smoking a cigarette. Go Gyi Gyo! The crowd roared its approval.

Pine’s body flowed in undulating movements to the music, arms held aloft, hands snapping up and down. There was a controlled urgency to his movements, as if, at any moment, he might break into a frenzy. He grabbed two terrified boys from the crowd, placing them on the ground where they faced each other.

“Which of these fighting oxen will win?” he asked the crowd in a deep bass voice that sounded distinctly unlike the voice of the man I had just spoken with. Everyone let up a yell. Men jumped forward to wager on the boys, pressing bills into his hands. Go Gyi Gyo reigned haughtily over the proceedings, hands on his hips, eyes leveled defiantly on the crowd. “Place your bets! Come on! What are you waiting for?”

When adequate wagers had been collected, Go Gyi Gyo put a bottle of grain alcohol to each boy’s lips. After they took a long draught and were left panting, he slashed a hand through the air to commence the match. The boys locked head-to-head, each straining to push the other out of the arena. The crowd cheered and jostled for a better view. At last, one boy was forced to the side of the hut and Go Gyo Gyo ended the match with a wave of his hand.

“Do good things!” he admonished, throwing money into the crowd. People dived past me for the bills, a great mass of bodies pushing and tearing at each other. The melee ended as quickly as it had erupted, torn pieces of money lying like confetti upon the ground. Go Gyi Gyo was gone, and for once the band fell to silence.

The music soon recommenced at a feverish pitch. Several performers emerged to announce the grand finale of the festival: the spirit possession ceremony. They now called for appearance of two special spirits, the Shan Brothers. Though outside the main pantheon of the 37, the spirits were the ancestral guardians of the hut’s owner, Zaw, who hoped to secure their blessings and protection for the future—but this could only happen if the spirits successfully possessed members of his family.

Pine, as head nat-kadaw, seized two women from the crowd—Zaw’s wife and her sister. He handed them a sacred rope attached to a spirit pole, ordering them to tug on it. As the frightened women complied, they bared the whites of their eyes and began shaking. Shocked as if with a sudden jolt of energy, they started a panicked dance, twirling and colliding into members of the crowd. On-lookers fled, pressing against the walls of the hut to try to escape. The women, seemingly oblivious to what they were doing, stomped to the spirit altar, each seizing a machete.

“Uh-oh,” I said to Jiro, who was already trying to climb over the back of our bench.

The women waved the knives in the air, dancing only a few feet away from me. Just as I was considering my own quickest route of escape, they collapsed to the ground, sobbing and gasping. The nat-kadaws ran to their aid, cradling them, and the women gazed with bewilderment at the crowd.

“Do you remember what just happened?” I had Jiro ask the wife.

She looked at me as if she had just woken from a dream. “No,” she whispered. Her face looked haggard, her body lifeless. Someone helped lead her away.

As the women had been successfully possessed, Pine prepared to send all the nats back to the spirit realm and end the ceremony. He and the other nat-kadaws made final food offerings to the statues. Zaw, as the house owner and wealthy sponsor of the ceremony, brought out two of his children to “offer” to the spirits as a representation of the new generation. Pine encircled the family with the sacred spirit rope, saying a prayer for their wealth and happiness. But the ceremony wasn’t complete without the crowd making an entreaty to the Buddha, asking that the merit of the ceremony extend to all beings.

Pine went beneath the stage to change. Though the other dancers stayed dressed as women, he reappeared with his long hair tied back, in a black T-shirt, and began to pack up his things. The drunken crowd hooted and cruelly cat-called him and the members of his troupe, but Pine looked unfazed. I wondered who pitied who. The next day, he and his dancers would be gone from That Yar Gone, a small fortune in their pockets. Meanwhile, the white sun would rise sharply over the village, and the people in the crowd would be back to finding ways to survive along the river.

*

Greenery gradually replaced the desert scrub of the Dry Zone, until we finally arrived in the sultry heat of the Delta Region. We approached the last major town on the Irrawaddy, Moulmeingyun, its banks crowded with teak vessels colorfully painted as if in imitation of the vibrant hues of the tropics. On the docks, a frowning, well-dressed man in glasses stared at me: the local authorities. Jiro went out to greet him, then returned to tell me that we had a problem—someone had forgotten to list Moulmeingyun on my special permit: I was there illegally. As was the case with many other sensitive areas of Myanmar, much of the Delta was off-limits to tourists.

I had been with Jiro long enough by now to know when he was nervous. He stood straighter; he made unnatural, obsequious shows of respect. As he disappeared to discuss my situation with the authorities, I waited in the boat, my body pulsing with apprehension. Did I journey over 1,300 miles on the Irrawaddy to have to turn back now, only one day from my goal? Crowds of men gathered on the dock to look at me, as if I were a zoo specimen. The sun’s departure left deepening shadows, the night arriving with finality.

Jiro returned with the news. We wouldn’t be able to camp along the Irrawaddy tonight; we would be staying in the town’s rest house. It was not a choice, I knew, but an ultimatum. We headed there immediately, and the receptionist ushered me into a small cement-walled cubicle, filthy, reeking of urine, feeling stiflingly hot. The bed sheets, perhaps never washed before, displayed blood and other bodily stains. As Jiro left me to report to the police station, I sat on the

very edge of the bed, sighing. I was exhausted, and shaking from fear and frustration. All I had wanted to do was travel down a river, from its beginning to its end. It had seemed an innocent, simple venture. I was no human rights investigator. No pro-democracy disseminator. But true innocence was irrelevant in a country like Myanmar.

The heat was stifling. I left the room and walked outside. I had only reached the street when someone came running after me, shouting. It was the receptionist.

“You! Go back inside! You!”

I stopped, sighed. “What’s the problem now?” I asked him.

My question seemed to infuriate him even more. “Go to room now!” he shouted, clapping his hands.

But the cool air felt too good. I lingered in it for a few more moments, the receptionist hopping in fury at my obstinacy. When I finally returned to the room, I found that a grim-looking man had stationed himself in a chair outside, glaring at me.

*

I had expected my trip to end in Moulmeingyun, but the local authorities acquiesced: they would allow me to go to the sea. I wanted nothing more than to finally reach it. We sped off in a motorboat well before dawn, the town vanishing into the darkness behind us. I’d gotten no sleep, the heat of my room nearly unbearable, but now I could bask in the cool wind rising from the surface of the Irrawaddy. Glorious river, bringing blessings to the people.

The sun rose as pure orange light over the mangrove swamps and jungle. As we traveled down the last few miles of the Irrawaddy, I hoped to find a kind of innocence to replace my experience of the previous night. We arrived at villages where the people clustered around me with rapt attention, eager to know who I was, where I had come from. The children would hold their palms together reverentially to receive my offerings of candy. But then a man would appear. The same kind of man each time, walking over-confidently, dressing well, sometimes carrying a walky-talky. He was the village authority, warned by radio that I would be coming, and making it his duty to shadow me.

We traveled further on the river, until it broke open to the sea. Large whitecaps struck and rocked our tiny boat. Sunlight dazzled the churning waters, my thermometer reading 119F degrees—the hottest day of my trip. The heat felt staggering, as if the weight of the white sky were about to collapse upon me. We puttered slowly toward a distant spit of land crowned with a golden stupa: Eya village. The last village on the Irrawaddy.

The end of my trip.

As we docked beside a pristine white beach, I traded the sight of the Irrawaddy for the aquamarine waves of the Andaman Sea. Palm trees languished in the breeze. Canoes dotted the water, where men dived for scallops. They were Eya’s biggest in-country export; each ten-pound sack of shells—sold as fodder to chicken farms—would net the equivalent in Myanmar kyat of twelve cents.

Eya seemed to offer me the innocence I had been looking for. No men with walky-talkies appeared. No one seemed to mind that I was there. None of the people—neither young nor old—had ever seen a white person before. From the thatch huts raised on stilts, they climbed down to get a good look at me. They had seen a man from China a few times, they said, but never someone who looked like me.

“We have a beautiful life,” one woman volunteered. “We can get money from the Irrawaddy and the sea.”

And they had a special job, too: they rescued passing Shinupagoda rafts, putting the statues inside in a special shrine in the village. As saint of the Irrawaddy, apparently Shinupagoda wasn’t meant to enter the sea. Nor was I. I was ready to go home.

Though the Burmese government had denied that the great tsunami of late 2004 affected mainland Myanmar, Eya’s villagers told me that it had struck their village. An old woman, her eyes wide, spoke about seeing the coming of the great waves, everyone in Eya fleeing inland. She pointed at their golden stupa. “The Lord Buddha protected us from the tsunami,” she said. “No one in Eya died.” But the people on nearby Kaingthaung Island, which sat in the mouth of the Irrawaddy, had not been so fortunate. The waves had covered half the island, she said, killing seven or eight people.

As I walked through Eya, down its narrow spit of land completely exposed to the sea, I missed the security of being on the Irrawaddy, which, for all of its heat and mercurial moods, felt like the only safe place of my entire trip. Still, Eya had been spared from the great waves. No one here had died. It seemed like a true miracle.

In the distance, a man was approaching me on a bicycle. He was well-dressed. Intent on reaching me.

No. Not even in Eya.

|

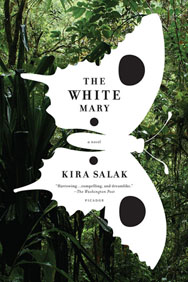

THE WHITE MARY

by Kira Salak

"A gripping debut novel."

Publishers Weekly Pick-of-the-Week

"There aren't many books that we hand to friends, urging,

'You have to read this.' The White Mary is one of them."

Cleveland Plain Dealer

"Riveting."

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

"With The White Mary, journalist Kira Salak makes a stunning

debut as a novelist. This is a story whose beauty and power

sweeps you along, like the jungle rivers that bear her heroine

into the heart of New Guinea in search of a vanished American."

--Philip Caputo

|

© 2008 Kira Salak, KiraSalak.com--all rights of reproduction in any form reserved

![]()